-

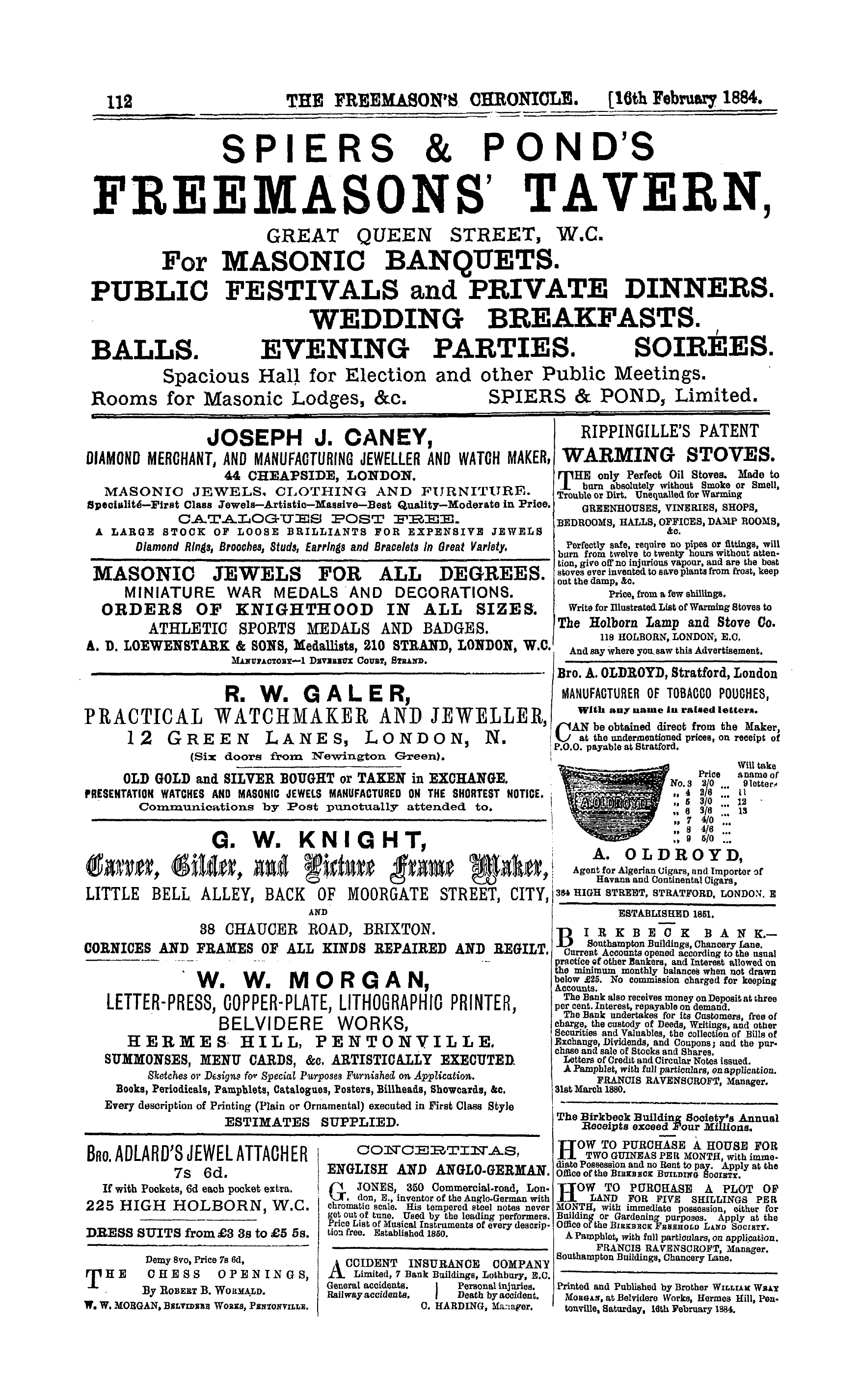

Articles/Ads

Article HISTORY OF FREEMASONRY. ← Page 3 of 3 Article HISTORY OF FREEMASONRY. Page 3 of 3 Article MASONRY, VIEWED BY AN ENGLISH BARRISTER. Page 1 of 1 Article MASONRY AMONG THE ARABS. Page 1 of 1

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

History Of Freemasonry.

met with in that ancient manuscript , I , for one , shonld have expected to find in a document of this character relating to artificers of the counties—written between 1427 and 1444 —some reference or allusion to the justices of the peace , whose authority was gradually being extended , by whom ,

no doubt , many regulations were made which have not survived , and who , by charters , letters patent , and ordinances of the reigning King—not entered on the Statute Roll—must have been constantly charged with the proper execution of the Statutes of Labourers in particular counties where their provisions had been evaded . "

In 1429 this enactment was made permanent by 8 Hen . VI . c . viii ., by which it was also ordained " that the ancient manner , form , and custom of putting and taking of apprentices , used and continued in the city of London , be from henceforth kept and observed . " In 1437 by

15 Hen . VI . c . yi ., 1436-7 , it was " sought to control a system which the legislature was powerless to repress " and " on the ground that 'the Masters , Wardens and people of many guilds , fraternities , and other companies , make among themselves many unlawful and unreasonable

ordinances of things ( inter alia ) ' which sound in confederacy ( sorment en confederacie ) for their singular profit , and common damage to the people , ' " it was ordered that all letters patent and charters should be " exhibited to the justices in counties , or the chief governors of cities ,

boroughs , and towns , without whose sanction no new ordinances were to be made or used , and by whom the same could be at any time revoked or repealed . " In 1444-5 , there was further legislation on the subject , and the wages of labourers and artificers were again assessed , those of a "free mason "—or "frank mason" —or master carpenter

" being limited to 4 d a day , with meat and drink , and 5 d without , and their winter wages to 3 d and 4 d respectively . " Bro . Gould , however , is not of Kloss ' s opinion that on the strength of this law—28 Henry VI . c . xii . —the Halliwell poem could not have been written after this date .

We are next taken through the legislative measures relating to " liveries , " and in treating of those which belong to the reign of Henry VII ., Bro . Gould notices a very conspicuous error , by which the words , " signs , " and " tokens " occurring in certain of them have been interpreted

to mean " signs of recognition and grips of salutation . " On this point the author quotes from Pike ' s " History of Crime in England " the following passage : " Nothing indicated more clearly that the elements of society were about to be thrown into new combinations than the

perseverance with which previous statutes against giving liveries and tokens were enforced , and with which their deficiencies were made by new enactments . All the considerable landholders still regarded themselves as chieftains . All their inferiors in their neighbourhood were

their retainers , to whom they gave liveries and tokens , and who , in other words , wore their uniform , and rallied to their standard . A common gift from chief to retainer

seems to have been a badge ( sign ) to be worn in the cap . Thus one of the Stanleys was in the habit of giving to his followers ' tho eagle ' s foot , ' and one of the Darcies ' the buck ' s head . ' These tokens were sometimes of silver and

sometimes gilfc , and were , no doubt , highly prized by those . who received them . " Thus , as Bro . Gould says , the " signs and tokens " mentioned in the Statute 11 Henry VII . c . iii . were " badges aud cognizances , " the former being the " masters' device , crest , or arms , on a separate piece of

cloth—or , in the time of Elizabeth , on silver—in the form of a shield , worn on the left sleeve by domestics and retainers , and even by younger brothers , who wore the badge of the elder ; " while the latter " were sometimes knots or devices worn in the caps or on the chest . "

Among other enactments mentioned is the 2 and 3 Edward VI . c . xv ., A . D . 1548 , which is the last that relates " to combinations and confederacies to enhance the wages of labour , " and which , in the opinion of Brentano , " does not refer at all to combinations similar to those of

our working men of the present day , but is simply an attempt to check the increasing abuses of the craft guilds . " There is also mentioned , and a synopsis of its provisions given , of 5 Eliz . c . iv ., frequently referred to as the " Statute of Apprentices . " In the 30 th clause of this it is

pointed out that though in previous statutes the term " Freemason " is used , here the solitary definition given is "rough Mason , " on which Bro . Gould says , "Had the generic term ' masons' been used by the framers of the Statute , the inference would be plain—that it referred to both the superior and the inferior classifications of the

History Of Freemasonry.

trade ; but the employment of the expression , rough mason , in a code , moreover , so carefully drawn up , almost forbids the supposition that it was intended to comprise a higher class of workmen , and rather indicates that the term Freemason—as already suggested—though , perhaps , in

common or successive uso , applied to denote a stonecutter , a contractor , a superior workman , a passed apprentice or free journeyman , and a person enjoying the freedom of a guild or company , had then lost—if , indeed , it over possessed—any purely operative significance , and if for no

other reason , was omitted from the Statute as imparting a sense in which it would have generally been misunderstood . " This brings us to the end of tho second chapter of

this second volume . In our next paper we shall travel northward for the purpose of studying Freemasonry in its early aspects in Scotland . ( To be continued . )

Masonry, Viewed By An English Barrister.

MASONRY , VIEWED BY AN ENGLISH BARRISTER .

AN English baronet , one of the best lawyers known to the English bar , now more than three decades passed away—Sir William Follett—is said to have regarded the Masonic Institution as one of the most hallowed means of beneficence among the associations of earth .

Sir William was Attorney General of England when he had the following conversation with one who afterwards became a shining light in the great Brotherhood of Masons . This Brother reports as follows I—

In the course of conversation with Sir W . Follett , I inferred from a passing remark that he had become a Mason . I asked if my conclusion was correct . ' It is , ' was his reply ; ' I was initiated at Cambridge . ' Light had not then beamed npon myself ; and I expressed in scoffing

terms my astonishment . ' In your early struggles at the bar , ' remarked he , with quiet earnestness , ' you require something to reconcile you to your kind . Ton see so much of bitterness , and rivalry , and jealousy , and hatred , that you are thankful to call into active agency a system which

creates , in all its varieties , kindly sympathy , cordial and wide-spread benevolence and brotherly love . ' ' But surely , ' said I , ' you don't go the length of asserting that Masonry does all this ? ' ' And more ! The true Mason thinks no ill of his brother , and cherishes no designs against him . The

system annihilates parties . And as to censoriousness and calumny , most salutary and stringent is the curb which Masonic principles , duly carried out , apply to an unbridled tongue . ' ' Well , well you cannot connect it with religion ; you cannot say , or affirm of it , that Masonry is a religious

system ? ' ' By-and-by you will know better , ' was his reply . ' Now I will only say that the Bible is never closed in a Mason ' s Lodge ; that Masons habitually use prayer in their Lodges ; and , in point of fact , never assemble for any purpose without performing acts of religion . ' ' I gave you

credit , ' continued I , with a smile , ' for being more thoroughly emancipated from nursery trammels and slavish prejudices . ' . . 'Meanwhile , ' said he , 'is it not worth

while to belong to a Fraternity whose principles , if universal , wonld put down at once and for ever the selfish and rancorous feelings which now divide and distract society ? ' " —Keystone .

Masonry Among The Arabs.

MASONRY AMONG THE ARABS .

THE Master of University Lodge , at a celebration of the Winter Festival , at Oxford , England , related the following incident of the influence of Masonry among the Arabs . He confessed , he said , that he had formally been prejudiced against Freemasonry , but

experience abroad had convinced him of his error , and satisfied him that there was something in it beyond the mere name . He once had a friend who , with his crew , had been wrecked in the Persian Gulf , when an Arab chieftain came down to plunder them ,

but on his friend giving the Masonic signs , they were protected and taken to Muscat , where they were not onl y clothed and properly taken care of , but afterwards taken to Borneo . He knew that to be a fact , and it so satisfied him as to the merits of Masonry that he resolved to

embrace the first opportunity of enrolling himself among its members . That pledge he had redeemed ; and from the moment he had been initiated he had felt the deepest intero . it in the Institution , and the greatest desire to promote its interests and extend its benefits . —Hebreiv Leader .

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

History Of Freemasonry.

met with in that ancient manuscript , I , for one , shonld have expected to find in a document of this character relating to artificers of the counties—written between 1427 and 1444 —some reference or allusion to the justices of the peace , whose authority was gradually being extended , by whom ,

no doubt , many regulations were made which have not survived , and who , by charters , letters patent , and ordinances of the reigning King—not entered on the Statute Roll—must have been constantly charged with the proper execution of the Statutes of Labourers in particular counties where their provisions had been evaded . "

In 1429 this enactment was made permanent by 8 Hen . VI . c . viii ., by which it was also ordained " that the ancient manner , form , and custom of putting and taking of apprentices , used and continued in the city of London , be from henceforth kept and observed . " In 1437 by

15 Hen . VI . c . yi ., 1436-7 , it was " sought to control a system which the legislature was powerless to repress " and " on the ground that 'the Masters , Wardens and people of many guilds , fraternities , and other companies , make among themselves many unlawful and unreasonable

ordinances of things ( inter alia ) ' which sound in confederacy ( sorment en confederacie ) for their singular profit , and common damage to the people , ' " it was ordered that all letters patent and charters should be " exhibited to the justices in counties , or the chief governors of cities ,

boroughs , and towns , without whose sanction no new ordinances were to be made or used , and by whom the same could be at any time revoked or repealed . " In 1444-5 , there was further legislation on the subject , and the wages of labourers and artificers were again assessed , those of a "free mason "—or "frank mason" —or master carpenter

" being limited to 4 d a day , with meat and drink , and 5 d without , and their winter wages to 3 d and 4 d respectively . " Bro . Gould , however , is not of Kloss ' s opinion that on the strength of this law—28 Henry VI . c . xii . —the Halliwell poem could not have been written after this date .

We are next taken through the legislative measures relating to " liveries , " and in treating of those which belong to the reign of Henry VII ., Bro . Gould notices a very conspicuous error , by which the words , " signs , " and " tokens " occurring in certain of them have been interpreted

to mean " signs of recognition and grips of salutation . " On this point the author quotes from Pike ' s " History of Crime in England " the following passage : " Nothing indicated more clearly that the elements of society were about to be thrown into new combinations than the

perseverance with which previous statutes against giving liveries and tokens were enforced , and with which their deficiencies were made by new enactments . All the considerable landholders still regarded themselves as chieftains . All their inferiors in their neighbourhood were

their retainers , to whom they gave liveries and tokens , and who , in other words , wore their uniform , and rallied to their standard . A common gift from chief to retainer

seems to have been a badge ( sign ) to be worn in the cap . Thus one of the Stanleys was in the habit of giving to his followers ' tho eagle ' s foot , ' and one of the Darcies ' the buck ' s head . ' These tokens were sometimes of silver and

sometimes gilfc , and were , no doubt , highly prized by those . who received them . " Thus , as Bro . Gould says , the " signs and tokens " mentioned in the Statute 11 Henry VII . c . iii . were " badges aud cognizances , " the former being the " masters' device , crest , or arms , on a separate piece of

cloth—or , in the time of Elizabeth , on silver—in the form of a shield , worn on the left sleeve by domestics and retainers , and even by younger brothers , who wore the badge of the elder ; " while the latter " were sometimes knots or devices worn in the caps or on the chest . "

Among other enactments mentioned is the 2 and 3 Edward VI . c . xv ., A . D . 1548 , which is the last that relates " to combinations and confederacies to enhance the wages of labour , " and which , in the opinion of Brentano , " does not refer at all to combinations similar to those of

our working men of the present day , but is simply an attempt to check the increasing abuses of the craft guilds . " There is also mentioned , and a synopsis of its provisions given , of 5 Eliz . c . iv ., frequently referred to as the " Statute of Apprentices . " In the 30 th clause of this it is

pointed out that though in previous statutes the term " Freemason " is used , here the solitary definition given is "rough Mason , " on which Bro . Gould says , "Had the generic term ' masons' been used by the framers of the Statute , the inference would be plain—that it referred to both the superior and the inferior classifications of the

History Of Freemasonry.

trade ; but the employment of the expression , rough mason , in a code , moreover , so carefully drawn up , almost forbids the supposition that it was intended to comprise a higher class of workmen , and rather indicates that the term Freemason—as already suggested—though , perhaps , in

common or successive uso , applied to denote a stonecutter , a contractor , a superior workman , a passed apprentice or free journeyman , and a person enjoying the freedom of a guild or company , had then lost—if , indeed , it over possessed—any purely operative significance , and if for no

other reason , was omitted from the Statute as imparting a sense in which it would have generally been misunderstood . " This brings us to the end of tho second chapter of

this second volume . In our next paper we shall travel northward for the purpose of studying Freemasonry in its early aspects in Scotland . ( To be continued . )

Masonry, Viewed By An English Barrister.

MASONRY , VIEWED BY AN ENGLISH BARRISTER .

AN English baronet , one of the best lawyers known to the English bar , now more than three decades passed away—Sir William Follett—is said to have regarded the Masonic Institution as one of the most hallowed means of beneficence among the associations of earth .

Sir William was Attorney General of England when he had the following conversation with one who afterwards became a shining light in the great Brotherhood of Masons . This Brother reports as follows I—

In the course of conversation with Sir W . Follett , I inferred from a passing remark that he had become a Mason . I asked if my conclusion was correct . ' It is , ' was his reply ; ' I was initiated at Cambridge . ' Light had not then beamed npon myself ; and I expressed in scoffing

terms my astonishment . ' In your early struggles at the bar , ' remarked he , with quiet earnestness , ' you require something to reconcile you to your kind . Ton see so much of bitterness , and rivalry , and jealousy , and hatred , that you are thankful to call into active agency a system which

creates , in all its varieties , kindly sympathy , cordial and wide-spread benevolence and brotherly love . ' ' But surely , ' said I , ' you don't go the length of asserting that Masonry does all this ? ' ' And more ! The true Mason thinks no ill of his brother , and cherishes no designs against him . The

system annihilates parties . And as to censoriousness and calumny , most salutary and stringent is the curb which Masonic principles , duly carried out , apply to an unbridled tongue . ' ' Well , well you cannot connect it with religion ; you cannot say , or affirm of it , that Masonry is a religious

system ? ' ' By-and-by you will know better , ' was his reply . ' Now I will only say that the Bible is never closed in a Mason ' s Lodge ; that Masons habitually use prayer in their Lodges ; and , in point of fact , never assemble for any purpose without performing acts of religion . ' ' I gave you

credit , ' continued I , with a smile , ' for being more thoroughly emancipated from nursery trammels and slavish prejudices . ' . . 'Meanwhile , ' said he , 'is it not worth

while to belong to a Fraternity whose principles , if universal , wonld put down at once and for ever the selfish and rancorous feelings which now divide and distract society ? ' " —Keystone .

Masonry Among The Arabs.

MASONRY AMONG THE ARABS .

THE Master of University Lodge , at a celebration of the Winter Festival , at Oxford , England , related the following incident of the influence of Masonry among the Arabs . He confessed , he said , that he had formally been prejudiced against Freemasonry , but

experience abroad had convinced him of his error , and satisfied him that there was something in it beyond the mere name . He once had a friend who , with his crew , had been wrecked in the Persian Gulf , when an Arab chieftain came down to plunder them ,

but on his friend giving the Masonic signs , they were protected and taken to Muscat , where they were not onl y clothed and properly taken care of , but afterwards taken to Borneo . He knew that to be a fact , and it so satisfied him as to the merits of Masonry that he resolved to

embrace the first opportunity of enrolling himself among its members . That pledge he had redeemed ; and from the moment he had been initiated he had felt the deepest intero . it in the Institution , and the greatest desire to promote its interests and extend its benefits . —Hebreiv Leader .