-

Articles/Ads

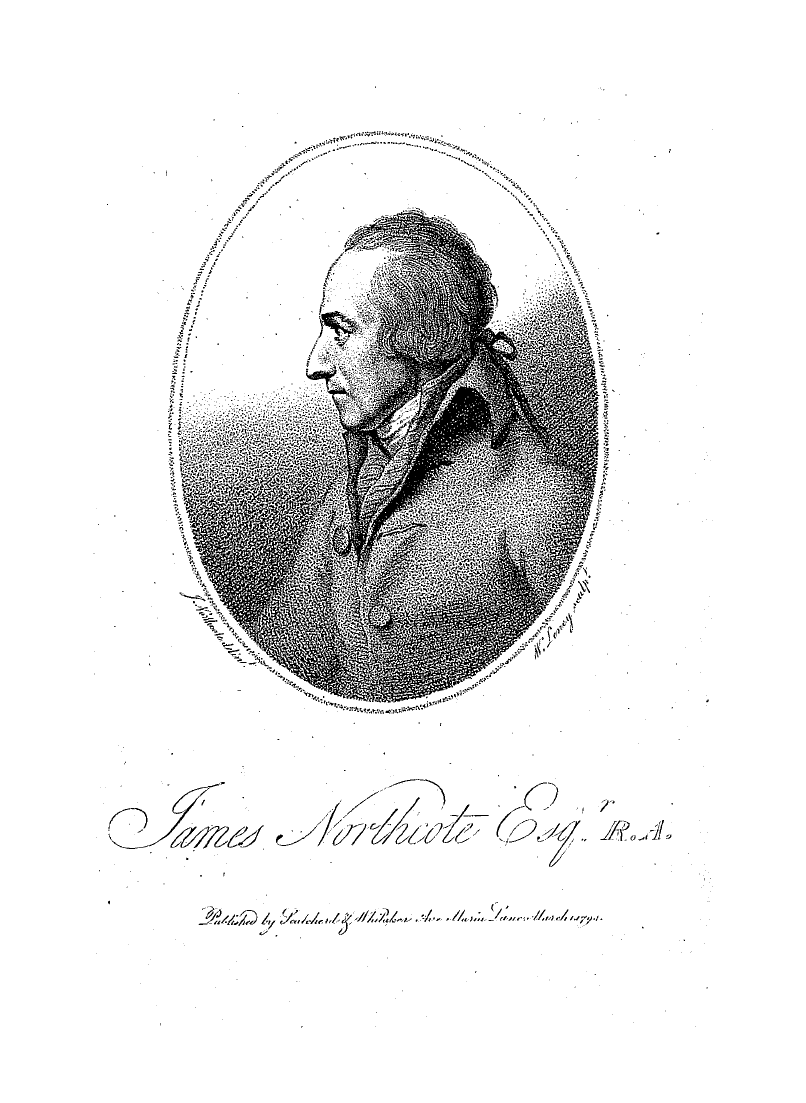

Article ON THE PROPRIETY OF MAKING A WILL. ← Page 3 of 5 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

On The Propriety Of Making A Will.

them distinctly—I mean , either putting off the making of a Avill to a distant and inconvenient period , or neglecting it altogether ; the latter perhaps sometimes is intentional , as in the case of a person who thinks he ought not to violate an imprudent promise in behalf of sortie one , Avhich would injure his heirs at laAv—but more often this proceeds from the first cause , a perpetual delay and backwardness to perform the most simple and act of human obligation

easy . It is not easy to' account for this backwardness in men of sense , for all the reasons assigned to excuse it are not very consistent with common sense . A man who is entitled , in any moderate degree , to the epithet of wife , will not surely think that when he signs his will , he signs his death-warrant , or that the undertaker must of necessity follow the lawyer . In fact it Avould be foolish to delay the making a will

even if this were the case , but surely that man ' s mind must have little fortitude , and less reli gion , who can at stated times think on death with composure , as that which is appointed for all men , and \ vhichhe can neither retard , nor accelerate . . But every thing must be subordinate to duty . If the thought of death be-a pain , it must be submitted to , because that which suggested

it is an obligation , binding on all men AVIIO are possessed of property , and much more on those who have families , and who are engaged in the connexions of business . Could any man of sense , who died Avithout a will , return to -see his family almost beggared , his children scattered on the' wide Avorld , his business embarrassed so as to be worth nothing , hoAv much would he be shocked to think that all this

confusion arose from his neglecting so simple an operation as a will t Would not such a man blush to find his memory despised , and perhaps execrated , for neglecting to do . what , if he considered a trifle , ought the . more readily to have been done , but what , considered as the means of avoiding ' much distress and confusion , it Avas criminal to leave undone ? '¦

One case . there is , which , I firmly believe , has prevented some men from making a will . It is not very honourable to human nature that such a cause should exist , but they who have opportunities of kno \ ving that it does exist , will not object to a truth , though an unwelcome one . I attribute the reluctance which Avorldly and avaricious men entertain against a will , to that extreme aversion they have to the very idea of parting Avith their property . As their enjoyment of wealth is not in

spending , but in hoarding , and is consequently a passion which brick-. dust might gratify if it were as scarce as gold-dust , it must be supposed that , the imaginary parting with their wealth will afflict them in proportion to the ecstasies that arise from their imaginary enjoyments . The miser who shows me his gold , has not much more enjoyment of it than 1-haye ; the bri ght metal affects my eyes just as much as his : the

employment of . the Avealth belongs to neither of us . I cannot touch it Avithout suffering punishment ; and he ' cannot Avithout suffering pain . I repeat it , that I am persuaded such a man ' will feel so much from the idea of parting Avith his Avealth , that he cannot sit down to give it aAvay with his own hand . I know not even whether a miser be not such a

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

On The Propriety Of Making A Will.

them distinctly—I mean , either putting off the making of a Avill to a distant and inconvenient period , or neglecting it altogether ; the latter perhaps sometimes is intentional , as in the case of a person who thinks he ought not to violate an imprudent promise in behalf of sortie one , Avhich would injure his heirs at laAv—but more often this proceeds from the first cause , a perpetual delay and backwardness to perform the most simple and act of human obligation

easy . It is not easy to' account for this backwardness in men of sense , for all the reasons assigned to excuse it are not very consistent with common sense . A man who is entitled , in any moderate degree , to the epithet of wife , will not surely think that when he signs his will , he signs his death-warrant , or that the undertaker must of necessity follow the lawyer . In fact it Avould be foolish to delay the making a will

even if this were the case , but surely that man ' s mind must have little fortitude , and less reli gion , who can at stated times think on death with composure , as that which is appointed for all men , and \ vhichhe can neither retard , nor accelerate . . But every thing must be subordinate to duty . If the thought of death be-a pain , it must be submitted to , because that which suggested

it is an obligation , binding on all men AVIIO are possessed of property , and much more on those who have families , and who are engaged in the connexions of business . Could any man of sense , who died Avithout a will , return to -see his family almost beggared , his children scattered on the' wide Avorld , his business embarrassed so as to be worth nothing , hoAv much would he be shocked to think that all this

confusion arose from his neglecting so simple an operation as a will t Would not such a man blush to find his memory despised , and perhaps execrated , for neglecting to do . what , if he considered a trifle , ought the . more readily to have been done , but what , considered as the means of avoiding ' much distress and confusion , it Avas criminal to leave undone ? '¦

One case . there is , which , I firmly believe , has prevented some men from making a will . It is not very honourable to human nature that such a cause should exist , but they who have opportunities of kno \ ving that it does exist , will not object to a truth , though an unwelcome one . I attribute the reluctance which Avorldly and avaricious men entertain against a will , to that extreme aversion they have to the very idea of parting Avith their property . As their enjoyment of wealth is not in

spending , but in hoarding , and is consequently a passion which brick-. dust might gratify if it were as scarce as gold-dust , it must be supposed that , the imaginary parting with their wealth will afflict them in proportion to the ecstasies that arise from their imaginary enjoyments . The miser who shows me his gold , has not much more enjoyment of it than 1-haye ; the bri ght metal affects my eyes just as much as his : the

employment of . the Avealth belongs to neither of us . I cannot touch it Avithout suffering punishment ; and he ' cannot Avithout suffering pain . I repeat it , that I am persuaded such a man ' will feel so much from the idea of parting Avith his Avealth , that he cannot sit down to give it aAvay with his own hand . I know not even whether a miser be not such a