-

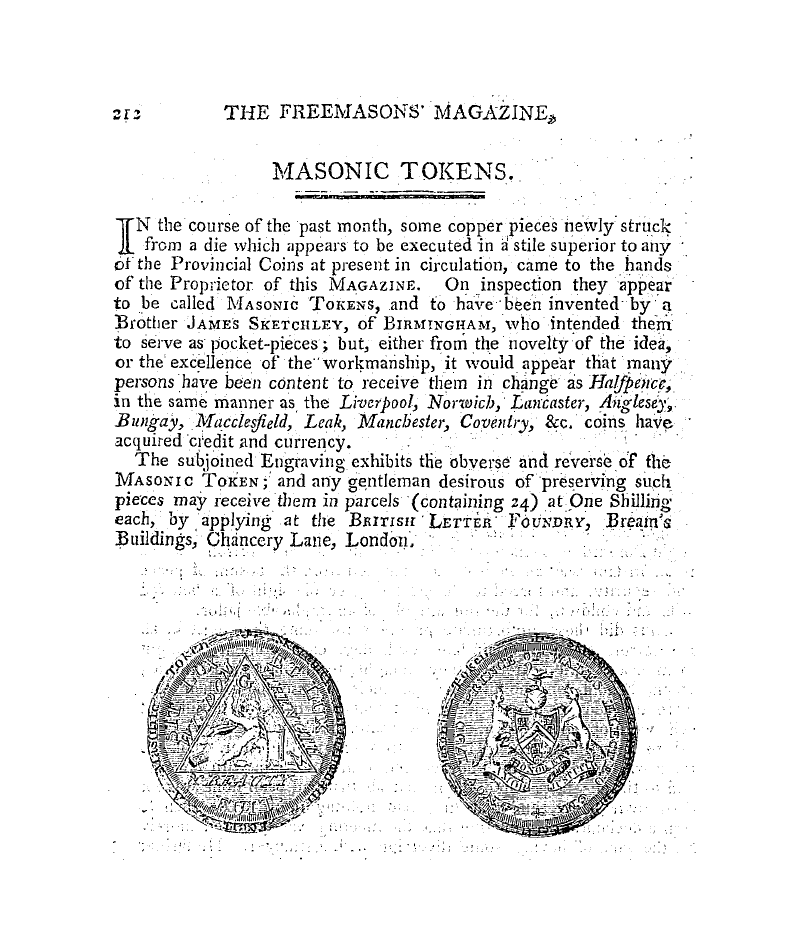

Articles/Ads

Article MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF ROBERSPIERRE. ← Page 5 of 10 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Memoirs Of The Life Of Roberspierre.

death , what he could not save by candour and fair-dealing ; he endeavoured to preserve by fraud and hypocrisy . There is a kind of infatuation which attends on ambition" ; and this laid strong hold of Roberspierre . If such were not the case he never would have ventured to the top of that very precipice from which he saw his predecessors hurled , either by the assassin ' s dagger , or the axe of faction . But so glaring is the ignis-fattens of powerthat the

, possession of it was the only object of his attention , and he looked on the glittering summit above with such earnestness , that he had not leisure to bestow a single glance on the ruins below . From his speech , however , some circumstances mi g ht be collected which plainly pointed out that he dreaded the effect of a calm ; when men ' s

minds , returning from the tempestuous sea in which they were then tossed , reason might resume the helm , and steer the dismasted vessel of state into a harbour of safety . His efforts , therefore , were wholly directed to assist , not to appease , the storm . There must be ho time for recollection—no moment for cool consideration . Tha breath of peace would be to him an atmosphere of annihilation . He lived onl y in the tempest of war . If he was not wicked before he

got into power , he found it necessary to become so how ; and therefore he .-4-ot rid of his conscience , that rapine and murder mig ht be pursued without remorse . Thus fortified against all the finer feelings ' of nature , he had nothing to apprehend from reflection ; and , as he had banished from his mind every idea of an hereafter , he rioted without a pang on the blood of his fellow-creatures .

Perhaps so complete a villain was never before moulded into the shape of a man ; and the terror which marked his expressions on the subject of moderatism proved that he was acquainted with his own character , and that he believed the bulk of mankind held that opinion of him . Hence . it was that he branded those with disaffection

to the state , Who did not pay homage ' to his system of governing ,, He knew that his views were partl y discovered , and that any thinglike solidity in administration , and permanence of constitution , must be his certain ruin , as well as the ruin of that party attached to bis ' interests . It was natural for him , therefore , to dread the cessation of hostilities , because , with die-establishment of peace must come the return of reason ; and a nation iu its sober senses would be a tribunal

of justice , from which Roberspierre could never escape with life . He seemed arrogantly to blame the people in France for attending to the character he bears in England , as if their judgment was only . to be directed by his opinion ; but ire pretty plainly proved from that circumstance that his enemies were ' numerous at home as well as abroad . He talked of the places he held as a personal burthen

that he bore merely for the benefit ofthe state ; but in this his veracity must be doubted by all who heard him , because it was well known by what villany he obtained , and with what art he endeavoured to hold them . His power , he was sensible , had received a shock , and it required more than all the art and . treachery he was master of to prevent it from total ruin . VOL , III . C c

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Memoirs Of The Life Of Roberspierre.

death , what he could not save by candour and fair-dealing ; he endeavoured to preserve by fraud and hypocrisy . There is a kind of infatuation which attends on ambition" ; and this laid strong hold of Roberspierre . If such were not the case he never would have ventured to the top of that very precipice from which he saw his predecessors hurled , either by the assassin ' s dagger , or the axe of faction . But so glaring is the ignis-fattens of powerthat the

, possession of it was the only object of his attention , and he looked on the glittering summit above with such earnestness , that he had not leisure to bestow a single glance on the ruins below . From his speech , however , some circumstances mi g ht be collected which plainly pointed out that he dreaded the effect of a calm ; when men ' s

minds , returning from the tempestuous sea in which they were then tossed , reason might resume the helm , and steer the dismasted vessel of state into a harbour of safety . His efforts , therefore , were wholly directed to assist , not to appease , the storm . There must be ho time for recollection—no moment for cool consideration . Tha breath of peace would be to him an atmosphere of annihilation . He lived onl y in the tempest of war . If he was not wicked before he

got into power , he found it necessary to become so how ; and therefore he .-4-ot rid of his conscience , that rapine and murder mig ht be pursued without remorse . Thus fortified against all the finer feelings ' of nature , he had nothing to apprehend from reflection ; and , as he had banished from his mind every idea of an hereafter , he rioted without a pang on the blood of his fellow-creatures .

Perhaps so complete a villain was never before moulded into the shape of a man ; and the terror which marked his expressions on the subject of moderatism proved that he was acquainted with his own character , and that he believed the bulk of mankind held that opinion of him . Hence . it was that he branded those with disaffection

to the state , Who did not pay homage ' to his system of governing ,, He knew that his views were partl y discovered , and that any thinglike solidity in administration , and permanence of constitution , must be his certain ruin , as well as the ruin of that party attached to bis ' interests . It was natural for him , therefore , to dread the cessation of hostilities , because , with die-establishment of peace must come the return of reason ; and a nation iu its sober senses would be a tribunal

of justice , from which Roberspierre could never escape with life . He seemed arrogantly to blame the people in France for attending to the character he bears in England , as if their judgment was only . to be directed by his opinion ; but ire pretty plainly proved from that circumstance that his enemies were ' numerous at home as well as abroad . He talked of the places he held as a personal burthen

that he bore merely for the benefit ofthe state ; but in this his veracity must be doubted by all who heard him , because it was well known by what villany he obtained , and with what art he endeavoured to hold them . His power , he was sensible , had received a shock , and it required more than all the art and . treachery he was master of to prevent it from total ruin . VOL , III . C c