-

Articles/Ads

Article A VIEW OF THE PROGRESS OF NAVIGATION. ← Page 3 of 6 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

A View Of The Progress Of Navigation.

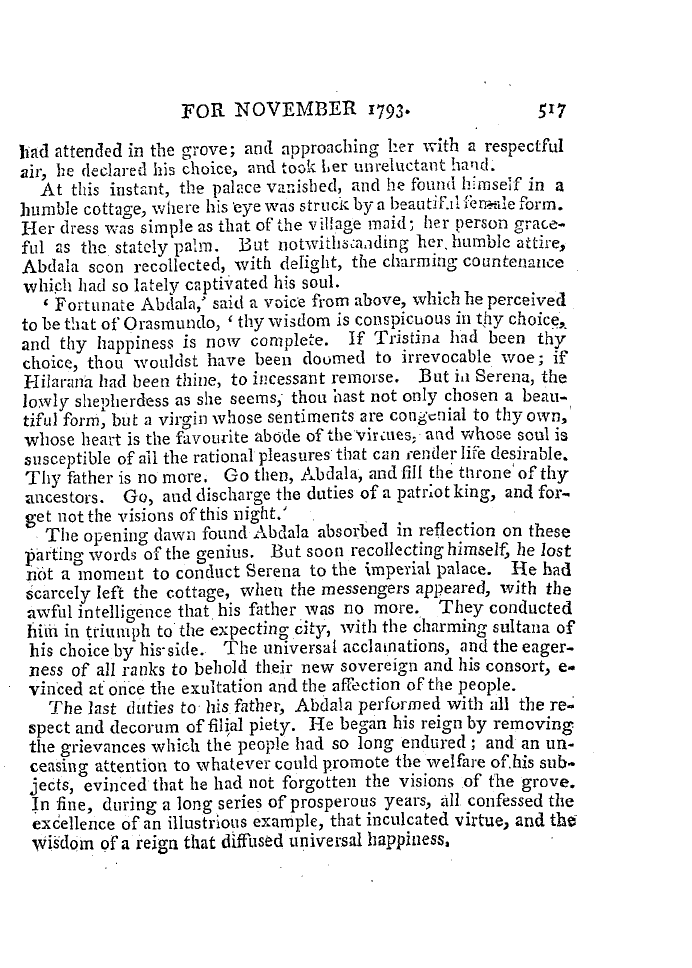

but when forced , as they must often have been , into the open sea , how they have directed their course is unknown . They were ignorant of any method of taking the meridian altitude of the sun . In the night , indeed , they were accustomed to observe the stars , and particularly the Great Bear , the principal guide of the Grecian navigators . The uncertainty , and the dangers of steering their course by a constellation , which indicates with so little precision the north

pole , were augmented by the defective manner in which they made their observations . They were taken with the naked eye only . Still less were they acquainted with sea-charts . How then could they steer with any certainty to their intended port ? how avoid the rocks and-shoals that lay in their way ? What must have been their embarrassment , when overtaken by a tempest , especially in dark

and hazy weather , when the stars were clouded from their view ! Hence we find , that Homer always brings his subtle hero to land , absolutely ignorant of the very name of the coast on which he finds himself arrived * . They were also ignorant , at the period of which I now speak , of several machines that appear , to us indispensibly necessary to

navigation . In the time of the Argonauts they were unacquainted with the anchorf- It is even extremely doubtful whether it was known in the age of Homer ; at-least the Greek word properly signifying an anchor never once occurs in his poems , nor is there a single allusion to its use . The Greeks , it . would appear , made use at that time of large stones instead of anchors . When Ulysses arrived at the road of the Lestrigons , he attached his bark to a rock with . cables . t . ' ¦

There is also every reason to believe that they were utterly unacquainted with the practice of founding . Homer at least never men-tionsit ; we find nothing elsewhere to contradict the conclusions drawn from his silence . Plence we may easil y conceive the dangers to which , in the heroic times , the Grecian navigators were exposed . With so slender a stock of naval skillit was impossible they

, could extend their navigation to any considerable distance . In fact , it was not till six hundred years after the Argonautic expedition , that the Greeks dared to enter into the ocean § , which they had long regarded as a sea to which there was no access . As to the Red Sea , and the Arabian and Persian Gul phs , there they were not seen till the days of Alexander the Great .

The inhabitants of the island of E gina may be regarded as the first . of the European Greeks who distinguished themselves bv their skill in maritime affairs . By their attention to their marine forces ,

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

A View Of The Progress Of Navigation.

but when forced , as they must often have been , into the open sea , how they have directed their course is unknown . They were ignorant of any method of taking the meridian altitude of the sun . In the night , indeed , they were accustomed to observe the stars , and particularly the Great Bear , the principal guide of the Grecian navigators . The uncertainty , and the dangers of steering their course by a constellation , which indicates with so little precision the north

pole , were augmented by the defective manner in which they made their observations . They were taken with the naked eye only . Still less were they acquainted with sea-charts . How then could they steer with any certainty to their intended port ? how avoid the rocks and-shoals that lay in their way ? What must have been their embarrassment , when overtaken by a tempest , especially in dark

and hazy weather , when the stars were clouded from their view ! Hence we find , that Homer always brings his subtle hero to land , absolutely ignorant of the very name of the coast on which he finds himself arrived * . They were also ignorant , at the period of which I now speak , of several machines that appear , to us indispensibly necessary to

navigation . In the time of the Argonauts they were unacquainted with the anchorf- It is even extremely doubtful whether it was known in the age of Homer ; at-least the Greek word properly signifying an anchor never once occurs in his poems , nor is there a single allusion to its use . The Greeks , it . would appear , made use at that time of large stones instead of anchors . When Ulysses arrived at the road of the Lestrigons , he attached his bark to a rock with . cables . t . ' ¦

There is also every reason to believe that they were utterly unacquainted with the practice of founding . Homer at least never men-tionsit ; we find nothing elsewhere to contradict the conclusions drawn from his silence . Plence we may easil y conceive the dangers to which , in the heroic times , the Grecian navigators were exposed . With so slender a stock of naval skillit was impossible they

, could extend their navigation to any considerable distance . In fact , it was not till six hundred years after the Argonautic expedition , that the Greeks dared to enter into the ocean § , which they had long regarded as a sea to which there was no access . As to the Red Sea , and the Arabian and Persian Gul phs , there they were not seen till the days of Alexander the Great .

The inhabitants of the island of E gina may be regarded as the first . of the European Greeks who distinguished themselves bv their skill in maritime affairs . By their attention to their marine forces ,