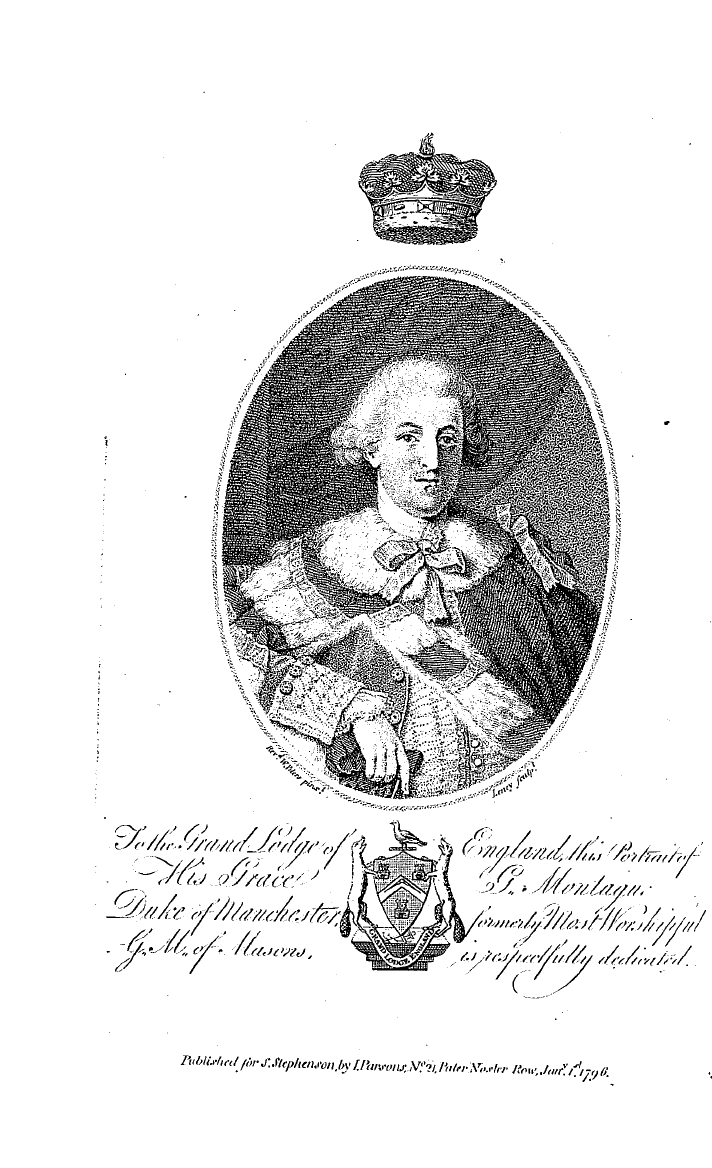

-

Articles/Ads

Article SKETCH OF THE CHARACTER OF Dr. ADAM SMITH. ← Page 2 of 3 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Sketch Of The Character Of Dr. Adam Smith.

struck , at the distance of years , with his accurate memory of the most trifling particulars ; and am inclined to believe , from fhis and some other circumstances ; that he possessed a power , not perhaps uncommon among absent men ; of recollecting , in consequence of subsequent efforts of . reflection , many occurrences which , at the time when they happened , did not seem to have , sensibl y attracted his notice . To . the defect now mentioned , it was probably owingin partthat

, , he did not fall in easily with the common dialogue of conversation ; and that he was something apt to convey his own ideas in the form of a lecture . When he did so , however ; it never proceeded from a wish to engross the discourse ; or to gratify his vanity . His own inclination disposed him so strongly to enjoy in silence the gaiety of those around him , that his friends were often led . to concert little

schemes , in order to bring him on the subjects most likel y to interest him . Nor do I think I shall be accused of going too far , when I say ; that he was scarcely ever known to start a new topic himself , or to appear unprepared upon those topics that were introduced by others . Indeed , his conversation was never more amusing than when he gave a loose to his genius ; upon the very few branches of knowledo-e of

Which he only possessed the outlines . . The opinions he formed of men ,, upon a sli ght acquaintance ; were frequently erroneous : but the tendency of his nature , inclined him much more to blind partiality , than to ill-founded prejudice . The enlarged views of . human affairs , on which his mind habituallydwelt , left him neither time nor . inclination to study , in detail , the

uninteresting peculiarities of ordinary characters ; and accordingly , though intimately acquainted with the capacities of the intellect ; and the workings of the heart , and accustomed in his theories , to mark , With the most delicate hand , the nicest shades , both of genius and of the passions ; yet , in judging of individuals , it sometimes happened , that his estimates were , in a surprising degree , wide of the truth . The opinionstoowhichin the thoughtlessness and confidence

, , , of his social hours , he was accustomed to hazard on books , and on questions of speculation , were not uniformly such as mi ght have been expected from the superiority of his understanding , and the singular consistency of his philosophical principles . They were liable to be influenced by accidental circumstances , and by the humour of the moment ; and when retailed bthose who onl

y y saw him occasionally , suggested false and contradictory ideas of his real sentiments . On these , however , as on most other occasions , there was always much truth , as well as ingenuity , in his remarks ; and if the different opinions which at different times he pronounced upon the same subject , Had been all combined together , so as to modif y and limit each otherthey would probablhave afforded materials

, y for a decision equally comprehensive and just . But , in the society of his friends , he had no disposition to form those qualified conclusions that we admire in his writings ; and he generally contented himself with a bold and masterly sketch of the object , from the first point of view in which his temper , or his fancy , presented it . Some-Vot .. V , jG

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Sketch Of The Character Of Dr. Adam Smith.

struck , at the distance of years , with his accurate memory of the most trifling particulars ; and am inclined to believe , from fhis and some other circumstances ; that he possessed a power , not perhaps uncommon among absent men ; of recollecting , in consequence of subsequent efforts of . reflection , many occurrences which , at the time when they happened , did not seem to have , sensibl y attracted his notice . To . the defect now mentioned , it was probably owingin partthat

, , he did not fall in easily with the common dialogue of conversation ; and that he was something apt to convey his own ideas in the form of a lecture . When he did so , however ; it never proceeded from a wish to engross the discourse ; or to gratify his vanity . His own inclination disposed him so strongly to enjoy in silence the gaiety of those around him , that his friends were often led . to concert little

schemes , in order to bring him on the subjects most likel y to interest him . Nor do I think I shall be accused of going too far , when I say ; that he was scarcely ever known to start a new topic himself , or to appear unprepared upon those topics that were introduced by others . Indeed , his conversation was never more amusing than when he gave a loose to his genius ; upon the very few branches of knowledo-e of

Which he only possessed the outlines . . The opinions he formed of men ,, upon a sli ght acquaintance ; were frequently erroneous : but the tendency of his nature , inclined him much more to blind partiality , than to ill-founded prejudice . The enlarged views of . human affairs , on which his mind habituallydwelt , left him neither time nor . inclination to study , in detail , the

uninteresting peculiarities of ordinary characters ; and accordingly , though intimately acquainted with the capacities of the intellect ; and the workings of the heart , and accustomed in his theories , to mark , With the most delicate hand , the nicest shades , both of genius and of the passions ; yet , in judging of individuals , it sometimes happened , that his estimates were , in a surprising degree , wide of the truth . The opinionstoowhichin the thoughtlessness and confidence

, , , of his social hours , he was accustomed to hazard on books , and on questions of speculation , were not uniformly such as mi ght have been expected from the superiority of his understanding , and the singular consistency of his philosophical principles . They were liable to be influenced by accidental circumstances , and by the humour of the moment ; and when retailed bthose who onl

y y saw him occasionally , suggested false and contradictory ideas of his real sentiments . On these , however , as on most other occasions , there was always much truth , as well as ingenuity , in his remarks ; and if the different opinions which at different times he pronounced upon the same subject , Had been all combined together , so as to modif y and limit each otherthey would probablhave afforded materials

, y for a decision equally comprehensive and just . But , in the society of his friends , he had no disposition to form those qualified conclusions that we admire in his writings ; and he generally contented himself with a bold and masterly sketch of the object , from the first point of view in which his temper , or his fancy , presented it . Some-Vot .. V , jG