Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

The Late Bro. Sirarthur Sullivan, Past Grand Organist.

The late Bro . Sir Arthur Sullivan , Past Grand Organist .

P rt / Ln r < fll C / uKUy

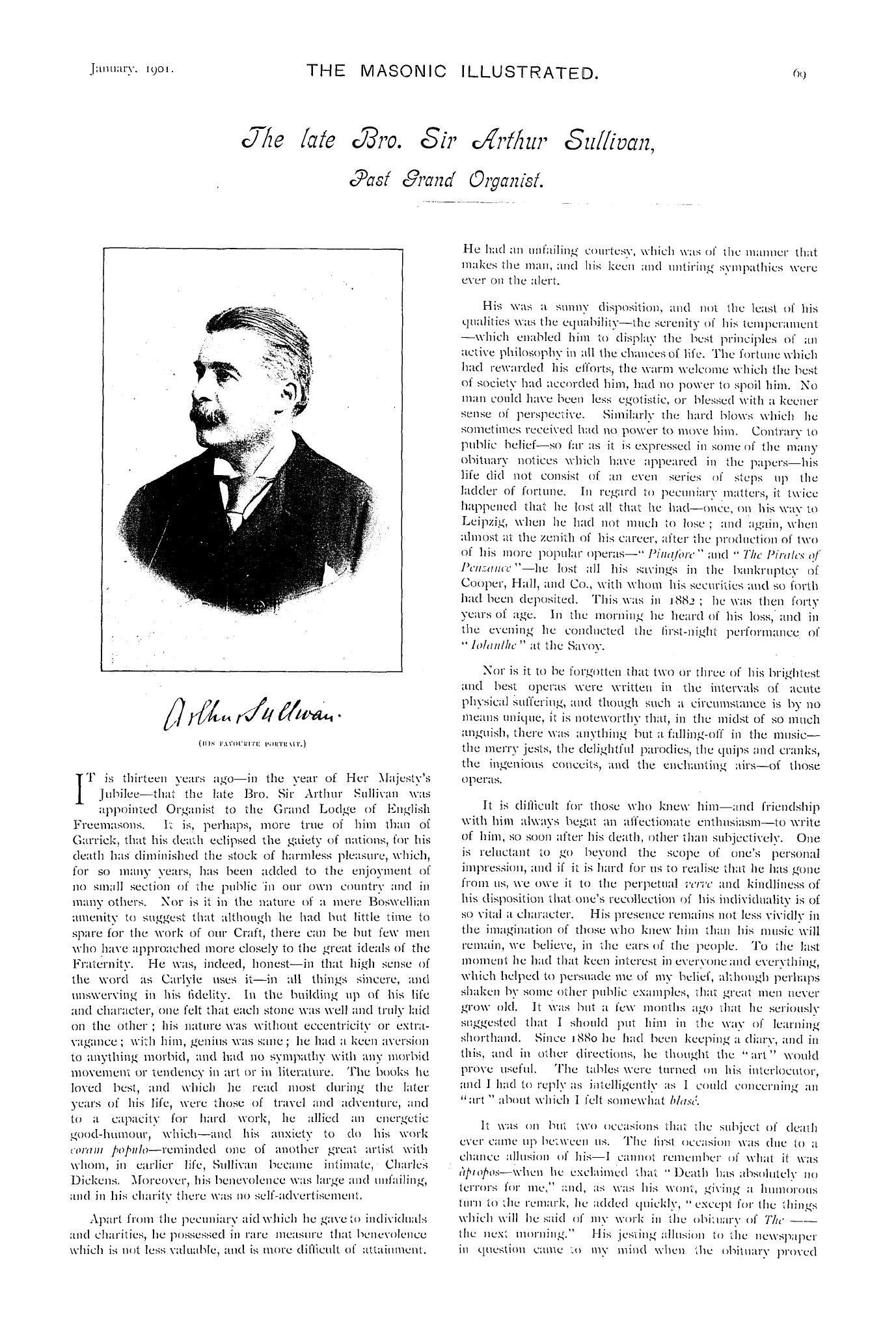

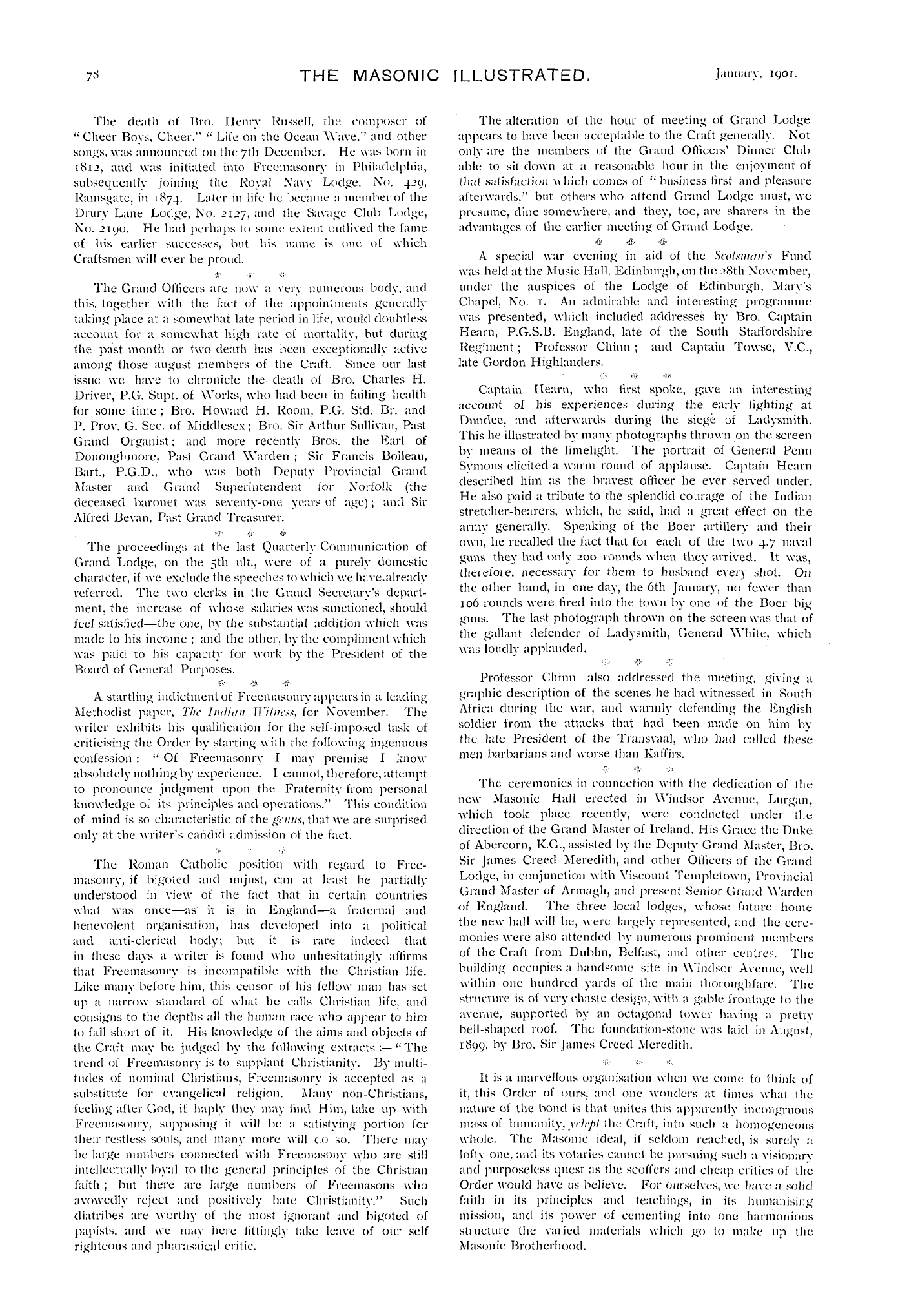

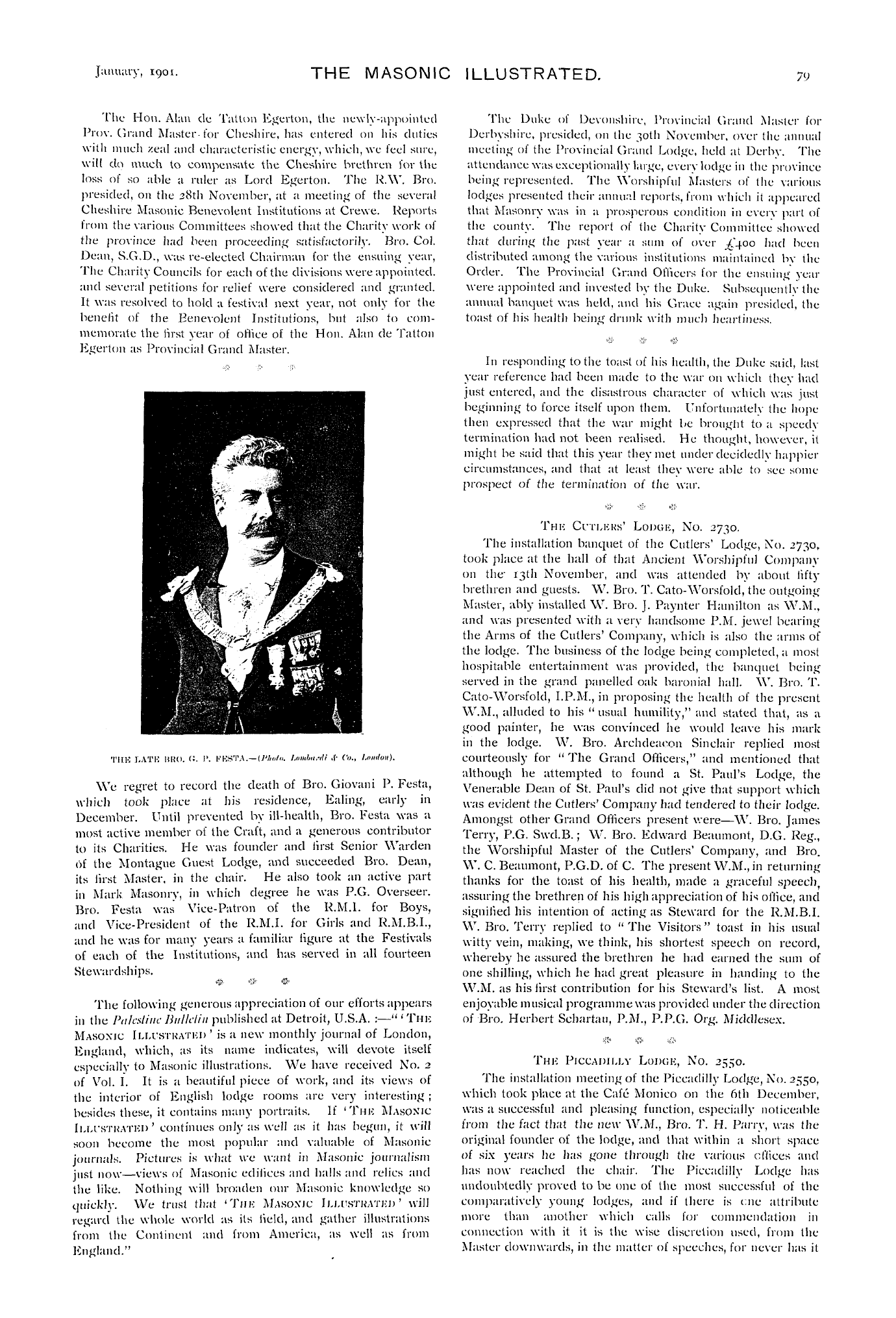

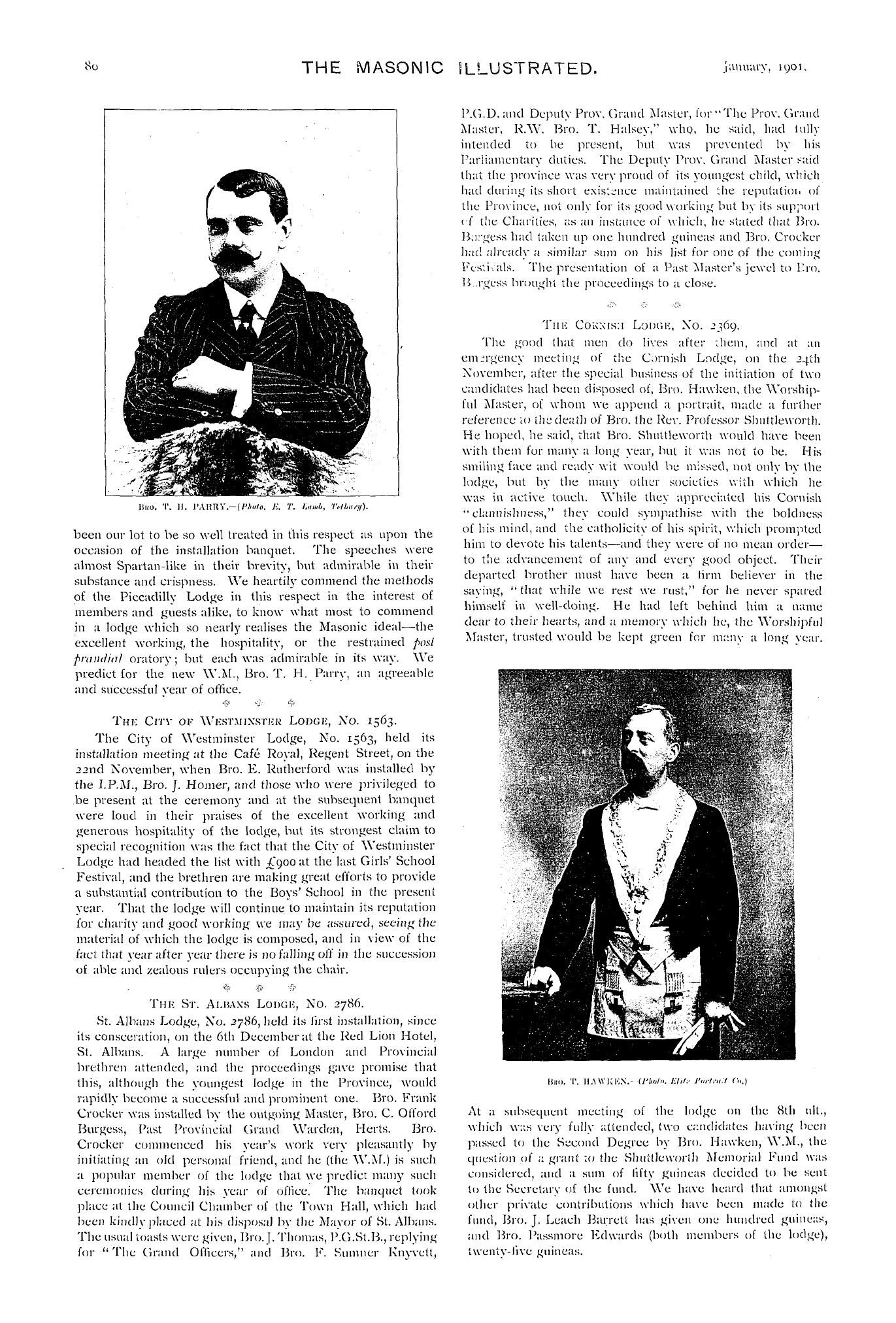

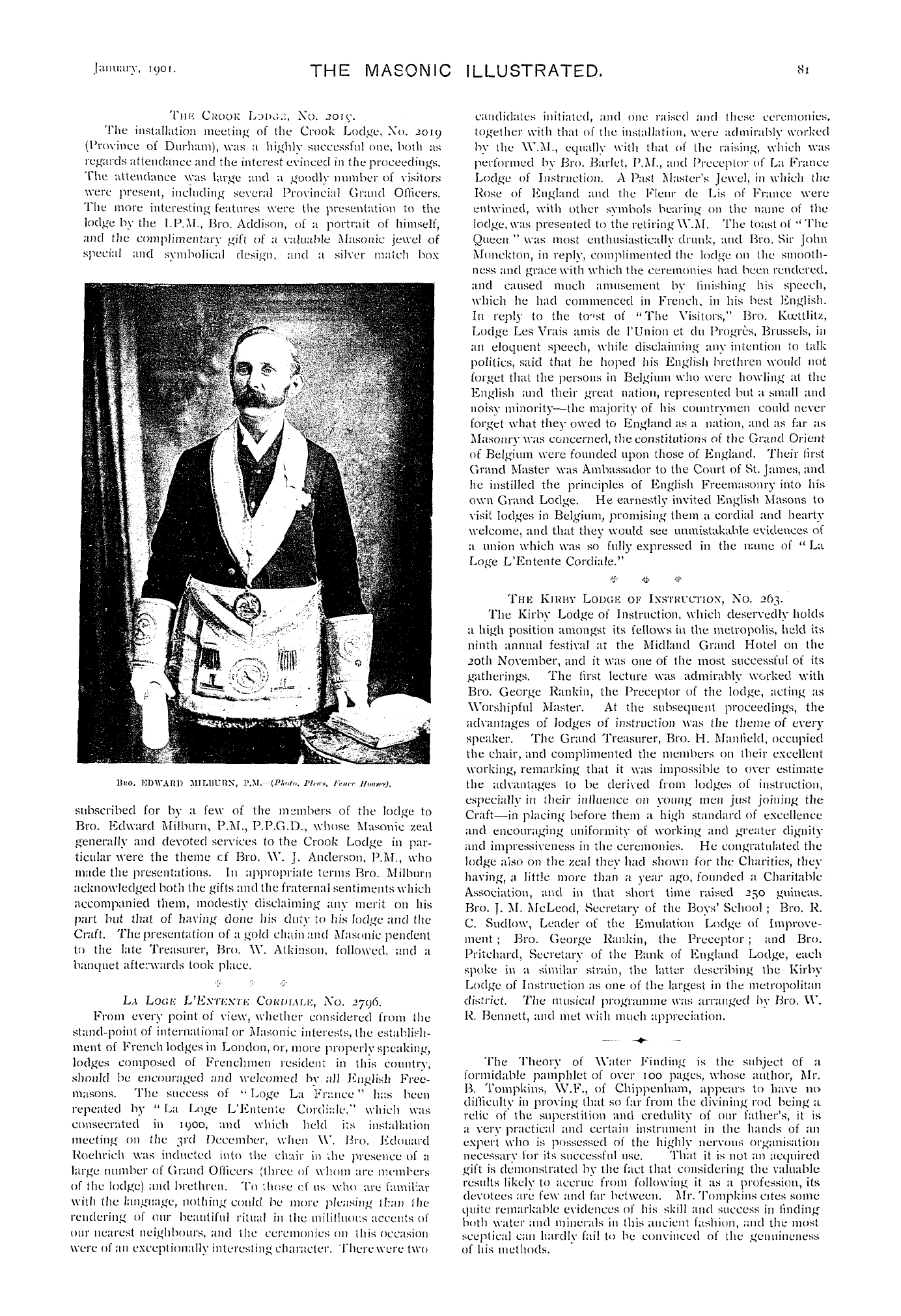

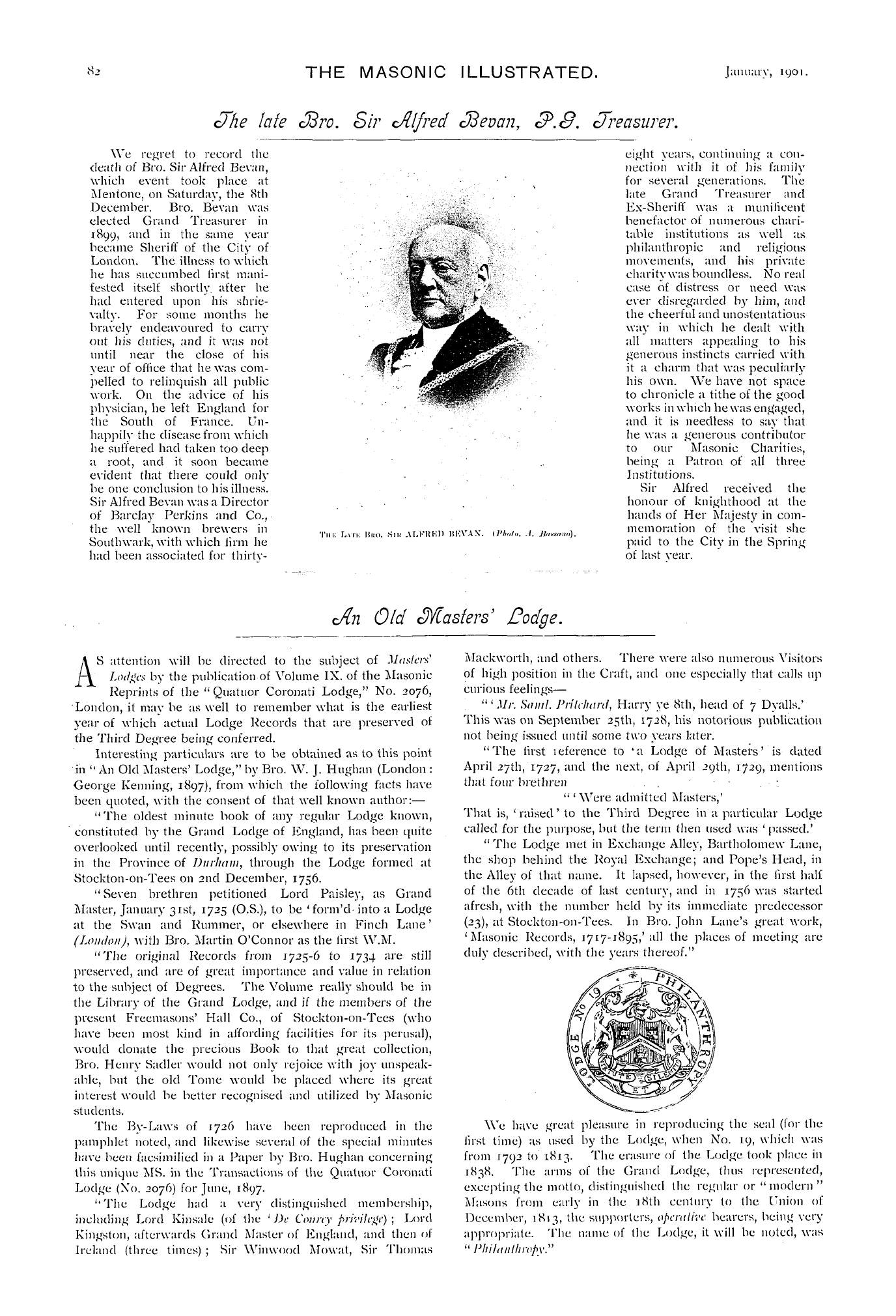

( Ills K . VVlll-UI' 1-K I'ilU'l'llUT . ) IT is thirteen years ago—in the year of Her Majesty ' s Jubilee—that the late Bro . Sir Arthur Sullivan was appointed Organist to the Grand Lodge of English

Freemasons . It is , perhaps , more true of him than of Garrick , that his death eclipsed the gaiety of nations , for his death has diminished the stock of harmless pleasure , which , for so many years , has been added to the enjoyment of no small section of the public in our own country and in many others . Nor is it in the nature of a mere Boswellian

amenity to suggest that although he had but little time to spare for the work of our Craft , there can be but few men who have approached more closely to the great ideals of the Fraternity . He was , indeed , honest—in that high sense of

the word as Carlyle uses it—in all things sincere , and unswerving in his fidelity . In the building up of his life and character , one felt that each stone was well and truly laid on the other ; his nature was without eccentricity or extravagance ; with him , genius was sane ; he had a keen aversion to anything morbid , -and had no sympathy with any morbid

movement or tendency in art or in literature . The books he loved best , and which he read most during the later years of his life , were those of travel and adventure , and to a capacity for hard work , he allied an energetic good-humour , which—and his anxiety to do his work

coram populo—reminded one of another great artist with whom , in earlier life , Sullivan became intimate , Charles Dickens . Moreover , his benevolence was large and unfailing , and in his charity there was no self-advertisement . Apart from the pecuniary aid which he gave to individuals and charities , he possessed in rare measure that benevolence which is not less valuable , and is more difficult of attainment .

He had an unfailing courtesy , which was of the manner that makes the man , and his keen and untiring sympathies were ever on the alert . His was a sunny disposition , and not the least of his qualities was the equability—the serenity of his temperament

—which enabled him to display the best principles of an active philosophy in till the chances of life . The fortune which had rewarded his efforts , the warm welcome which the best of society had accorded him , had no power to spoil him . No man could have been less egotistic , or blessed with a keener

sense of perspective . Similarl y the hard blows which he sometimes received had no power to move him . Contrary to public belief—so far as it is expressed in some of the many obituary notices which have appeared in the papers—his life did not consist of an even series of steps up the

ladder of fortune . In regard to pecuniary matters , it twice happened that he lost all that he had—once , on his way lo Leipzig , when he had not much to lose ; and again , when ¦ almost at the zenith of his career , after the production of two of his more popular operas— " Pinafore" and " The Pintles of

Penzance "—he lost all his savings in the bankruptcy of Cooper , Hall , and Co ., with whom his securities -and so forth had been deposited . This . was in 1882 ; he was then forty years of age . In the morning he heard of his loss , and in the evening he conducted the lirst-night performance of " lo / aullie " at the Savoy .

Nor is it to be forgotten that two or three of his brightest and best operas were written in the intervals of acute physical suffering , and though such a circumstance is by no means unique , it is noteworthy that , in the midst of so much anguish , there was anything but a falling-off in the

musicthe merry jests , the delightful parodies , the quips and cranks , the ingenious conceits , and the enchanting airs—of those operas .

It is difficult for those who knew him—and friendship with him always begat an affectionate enthusiasm—to write of him , so soon after his death , other than subjectively . One is reluctant to go beyond the scope of one ' s personal impression , and if it is hard for us to realise that he has gone

from us , we owe it to the perpetual verve and kindliness of his disposition tlv . it one ' s recollection of his individuality is of so vital a character . His presence remains not less vividly in the imagination of those who knew him than his music will remain , we believe , in the ears of the people . To the hist

moment he had that keen interest in everyone and everything , which helped to persuade me of my belief , although perhaps shaken by some other public examples , that great men never grow old . It was but a few months ago that he seriously suggested that I should put him in the way of learning

shorthand . Since 1880 he had been keeping a diary , and in this , and in other directions , he thought the "art" would prove useful . The tables were turned on his interlocutor , and I had to reply as intelligently as I could concerning an " art " about which I felt somewhat blase .

It was on but two occasions that the subject of death ever came up between us . The lirst occasion was due to a chance allusion of his—I cannot remember of what it was iipiopos—when he exclaimed that " Death has absolutely no terrors for me , " and , its was his wont , giving a humorous

turn to the remark , he added quickly , " except for the things which will he said of my work in the obituary of The the next morning . " His jesting allusion to the newspaper in question came to my mind when the obituary proved

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

The Late Bro. Sirarthur Sullivan, Past Grand Organist.

The late Bro . Sir Arthur Sullivan , Past Grand Organist .

P rt / Ln r < fll C / uKUy

( Ills K . VVlll-UI' 1-K I'ilU'l'llUT . ) IT is thirteen years ago—in the year of Her Majesty ' s Jubilee—that the late Bro . Sir Arthur Sullivan was appointed Organist to the Grand Lodge of English

Freemasons . It is , perhaps , more true of him than of Garrick , that his death eclipsed the gaiety of nations , for his death has diminished the stock of harmless pleasure , which , for so many years , has been added to the enjoyment of no small section of the public in our own country and in many others . Nor is it in the nature of a mere Boswellian

amenity to suggest that although he had but little time to spare for the work of our Craft , there can be but few men who have approached more closely to the great ideals of the Fraternity . He was , indeed , honest—in that high sense of

the word as Carlyle uses it—in all things sincere , and unswerving in his fidelity . In the building up of his life and character , one felt that each stone was well and truly laid on the other ; his nature was without eccentricity or extravagance ; with him , genius was sane ; he had a keen aversion to anything morbid , -and had no sympathy with any morbid

movement or tendency in art or in literature . The books he loved best , and which he read most during the later years of his life , were those of travel and adventure , and to a capacity for hard work , he allied an energetic good-humour , which—and his anxiety to do his work

coram populo—reminded one of another great artist with whom , in earlier life , Sullivan became intimate , Charles Dickens . Moreover , his benevolence was large and unfailing , and in his charity there was no self-advertisement . Apart from the pecuniary aid which he gave to individuals and charities , he possessed in rare measure that benevolence which is not less valuable , and is more difficult of attainment .

He had an unfailing courtesy , which was of the manner that makes the man , and his keen and untiring sympathies were ever on the alert . His was a sunny disposition , and not the least of his qualities was the equability—the serenity of his temperament

—which enabled him to display the best principles of an active philosophy in till the chances of life . The fortune which had rewarded his efforts , the warm welcome which the best of society had accorded him , had no power to spoil him . No man could have been less egotistic , or blessed with a keener

sense of perspective . Similarl y the hard blows which he sometimes received had no power to move him . Contrary to public belief—so far as it is expressed in some of the many obituary notices which have appeared in the papers—his life did not consist of an even series of steps up the

ladder of fortune . In regard to pecuniary matters , it twice happened that he lost all that he had—once , on his way lo Leipzig , when he had not much to lose ; and again , when ¦ almost at the zenith of his career , after the production of two of his more popular operas— " Pinafore" and " The Pintles of

Penzance "—he lost all his savings in the bankruptcy of Cooper , Hall , and Co ., with whom his securities -and so forth had been deposited . This . was in 1882 ; he was then forty years of age . In the morning he heard of his loss , and in the evening he conducted the lirst-night performance of " lo / aullie " at the Savoy .

Nor is it to be forgotten that two or three of his brightest and best operas were written in the intervals of acute physical suffering , and though such a circumstance is by no means unique , it is noteworthy that , in the midst of so much anguish , there was anything but a falling-off in the

musicthe merry jests , the delightful parodies , the quips and cranks , the ingenious conceits , and the enchanting airs—of those operas .

It is difficult for those who knew him—and friendship with him always begat an affectionate enthusiasm—to write of him , so soon after his death , other than subjectively . One is reluctant to go beyond the scope of one ' s personal impression , and if it is hard for us to realise that he has gone

from us , we owe it to the perpetual verve and kindliness of his disposition tlv . it one ' s recollection of his individuality is of so vital a character . His presence remains not less vividly in the imagination of those who knew him than his music will remain , we believe , in the ears of the people . To the hist

moment he had that keen interest in everyone and everything , which helped to persuade me of my belief , although perhaps shaken by some other public examples , that great men never grow old . It was but a few months ago that he seriously suggested that I should put him in the way of learning

shorthand . Since 1880 he had been keeping a diary , and in this , and in other directions , he thought the "art" would prove useful . The tables were turned on his interlocutor , and I had to reply as intelligently as I could concerning an " art " about which I felt somewhat blase .

It was on but two occasions that the subject of death ever came up between us . The lirst occasion was due to a chance allusion of his—I cannot remember of what it was iipiopos—when he exclaimed that " Death has absolutely no terrors for me , " and , its was his wont , giving a humorous

turn to the remark , he added quickly , " except for the things which will he said of my work in the obituary of The the next morning . " His jesting allusion to the newspaper in question came to my mind when the obituary proved