-

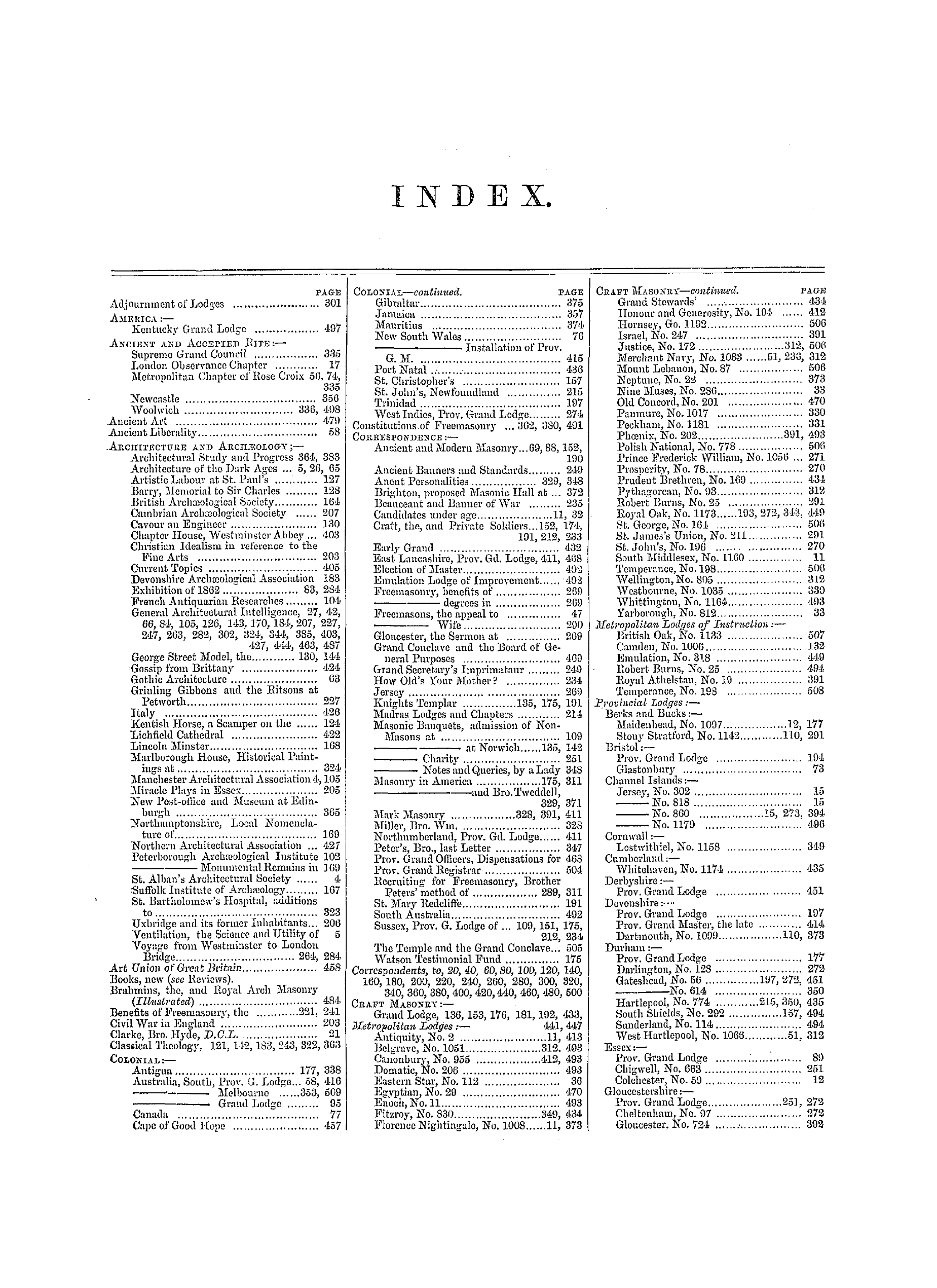

Articles/Ads

Article ARCHITECTURE AND ARCHEOLOGY. ← Page 3 of 3 Article ARCHITECTURE AND ARCHEOLOGY. Page 3 of 3 Article THE SCIENCE AND UTILITY OF VENTILATION. Page 1 of 2 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Architecture And Archeology.

by others still more comprehensii'e , and that each yielded up gracefully all that it had added to the general stock of ideas , to be grafted into the newer plant , to budaiid flourish again with fresh vigour and increase of poiver under a different regime . What , then , necessitated the artistic chaos Avhich reigned when JUediceval art A'anished ? What was the Gorgon ' s

head Avhich turned into stone the natural love for and poAver to originate beauty , which mankind had hitherto shown in all ages and countries ? These are the questions to which I am anxious to find a solution . The complete quenching of the lamp of art which , sooner or later in the period of the dark ages , ensued in every quarter of the globe—save where , among the less civilised

Oriental nations , it has stagnated until now in considerable decorative purity—is one of the strangest phenomena I am acquainted with in the history of the Avorld , and this I desire to invite you to consider , in the hope that we may be able to discover the rocks upon ivhich it was shipAvrecked , and that in our efforts to float it again we may be able to steer clear of them .

The "dark ages , " however , or , at least , the gloom of them , did not come on all at once . The night , unlike that of the tropics , did not folloiv suddenly the light of the Mediasval day . Nay , the sun of art set so gorgeously that men were dazzled by the glory thereof , and believed , thafc it was as sunrise , heralding a new , better phase of art , instead of its being a sunset , preluding the loss of the best the world had

seen . It behoves me , therefore , to linger over this threshold of my subject ( and nofc unwilling am I to do so , seeing that ifc is by far the pleasantest part thereof ) , and to endeavour to trace the lines of it several changes , as successively they grew fainter and fainter , together with the brightness of the evening stars of genius , which beamed like a galaxj '

through its twilight , and even occasionally long after the nightfall , until , clouded oi'er afc last , utter darkness unsued , enlivened only by the false Ai'ill-o ' -the-ivisp phantoms of rococo Avhich have been misleadina- men ever since .

This period , then , upon which I would now divell , this twilight of the "dark ages" which I ha \ r e taken for my subject , is that generally known as the Renaissance , or the revival of Classic art . It is true thafc in Italy , the whole surface of which was strewn with fragments of Roman work , Classic tradition seems always to hai'e sat like a nightmare upon its architecture . The mighty flood of life AA'hich

seems to have throbbed through the arteries of Northern Europe appears to have been checked in its passage through the gorges of the Alps , and to have exercised but slight effect below- them , and never entirely to haA'e succeeded in supplanting the influence of tho antique ; ifc succeeded in doing so to the greatest extent in the thirteenth century , and with much grace for a time fused the two stylesbut

, soon it began to hanker again after its old love , and Ave begin to find the mouldings of its Gothic buildings becoming poor ancl weak , and its parts and proportions betraying more of the Classic elements . In Venice , which , from its position , Avas nofc so strongly exposed to this influence , and which was greatly under ' that of J wth the Gothic and the

Byzantine , we find in the Doge ' s Palace a most valuable and nervous example of meditevatbuilding , unsurpassed in the boldness of its mouldings and detail ; yet , if Ave consider the general aspect of the domestic architecture of that city , Ave shall find little of the variety which was so marked a characteristic of Northern Gothic , it being similar detail to that of the Doge ' s Palace that we find repeated everyAvhere ,

ivhile that of tlie churches of the Erari and those of the same date arc strikingly inferior . In Verona we find another most valuable local development of Gothic , particularly artistic in its treatment of coloured material ancl sculpture ; still an under current of Classicism is evident throimhout Italian work . In the Cathedral of Milan it has debased it so far as to render it only worthof being a model for

y confectionery . _ In Florence and in Pisa AA'e are so entranced by the wealth displayed in their buildings , of painting and sculpture , aud precious coloured materials , that ive are consoled for the want of pure Medieval feeling and boldness in the handling of the architectural detail in such works thafc pretended to

Architecture And Archeology.

be Gothic , and in the host of false facades to the churches in the other towns , such as , we see figured in the plates of the works of Hope , Gaily Knight , and Street , we see foreshadoAved the childish shamelessness of sham ivhich mainly characterises the later works of the Renaissance , and those of tho " dark ages , " which ignores the certainty of beingfound out the instant the spectator turns the corner of the

building . In the Loggia de Lanzi , by Orcagna , Ave find distant traces of the Roman impost between the columns of the arches ; while his San Hichele , in the tabernacle and the tracery of the AvindoAvs , presents us with work , we might almost mistake for that of Batty Langley , In the pulpit by Andrew Pisano , in the cathedral of Pisa , we see in the figures and draperies of the bas-reliefs ,

evidences of an already too absorbing study of the antique , in contrast with the vigour shoivn in the beasts upon Avhich . - the alternate columns rest , where the sculptor has evidentlytreated them con amore , and rather with the traditional mediceval feeling , while fche capitals of the columns are almost as bad as the Roman composite , and the weedy apologies for cusped trefoil arches are the only and fadingtraces of Gothic forms . ( To be continued . )

The Science And Utility Of Ventilation.

THE SCIENCE AND UTILITY OF VENTILATION .

A lecture on this interesting topic was delivered at the Hanoversquare Rooms last week , by Professor Pepper , ivell known as the late scientific and enterprising conductor of the Polytechnic Institution , Regent-street . The fame of the lecturer and the importance of his subject brought together a numerous and fashionable audience , and the lecture was , in the hands of Professor Pepper , made to embrace the whole science of the subject of

ventilation in its relation to health and fche general condition of civilised , life . Tho lecturer commenced by referring to the history of A'enfcilation , and traced the tirsfc rude attempts of the Egyptians , the Grecians , and the Romans , many years before the beginning of the Christian era , to obtain \ -entilation and coolness in fche summer , and an escape for the smoke of their ( ires in the winter . Thus it appeared that the science of ventilation was early understood

, and earnest efforts ivere made to reduce it to practice by the learned men of those nations . The ancients made certain , apertures or holes in their buildings for the purpose of ventilation ; chimneys ivere not invented till about the twelfth or fourteenthcentury . Having thus complied with the . requirements of a historyloving people , Mr . Pepper proceeded to the broad and modernprinciples of ventilationivhich are based the well-knoivn

, upon law of the expansion of all bodies , solid , liquid , or gaseous , bobcat , and their contraction by cold . In illustration of this principle , a variety of interesting experiments were performed , exhibiting conclusively the action of this rigid and unswerving natural law , which , by the application of artificial means and contrivances , is made subservient to the necessities of civilisation . The importance of ventilation in its relation to human health .

was clearly pointed out and further illustrated by reference to an able paper written by Miss Florence Nightingale in the transactions of the Society for Promoting Social Science . This lady's hospital experience was most valuable in pointing out the necessit y for a continuous supply of fresh air , and plenty of it , for nothing could ' produce a more deleterious effect in the condition of the sick thana limited and impure supply of this healthy element . The danger of catching cold had been greatlexaggeratedmore especiallin a

y , y country like England , where fuel is cheap , and where the patient may be sufficiently protected by . an ample supply of clothing . Nothing could compensate for a deficient supply of air ; no artificial , means would suffice ; the only remedy was to throw open the windows , and so obtain a plentiful inlet of pure air . The hospitals in Paris , though ample , and even magnificent in their dimensions , Mr . Pepper pointed out , were incapable of conferring the whole of their and

possible intended advantages , from the simple reason that the ventilation was carried on by artificial means . In the morning , when the wards were opened , they were found to contain a close and vitiated atmosphere , which was sure to exercise an iinsalutary effect on the health of the patients . The simplest inventions in all matters of science were generally those of the widest practical utility . While discoveriesivhich had offered a broad field for

, every scientific researcher in the kingdom were floating in the minds of the astute and learned of all classes , Humphrey DaA-y electrified the savants hy the production of his miner ' s safety lamp , which was practicall y nothing more than an inclosure of the flame in a shade of fine wire gauze ; in fact , an application of a principle whose plainness and simplicity had rendered it an object of dis-

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Architecture And Archeology.

by others still more comprehensii'e , and that each yielded up gracefully all that it had added to the general stock of ideas , to be grafted into the newer plant , to budaiid flourish again with fresh vigour and increase of poiver under a different regime . What , then , necessitated the artistic chaos Avhich reigned when JUediceval art A'anished ? What was the Gorgon ' s

head Avhich turned into stone the natural love for and poAver to originate beauty , which mankind had hitherto shown in all ages and countries ? These are the questions to which I am anxious to find a solution . The complete quenching of the lamp of art which , sooner or later in the period of the dark ages , ensued in every quarter of the globe—save where , among the less civilised

Oriental nations , it has stagnated until now in considerable decorative purity—is one of the strangest phenomena I am acquainted with in the history of the Avorld , and this I desire to invite you to consider , in the hope that we may be able to discover the rocks upon ivhich it was shipAvrecked , and that in our efforts to float it again we may be able to steer clear of them .

The "dark ages , " however , or , at least , the gloom of them , did not come on all at once . The night , unlike that of the tropics , did not folloiv suddenly the light of the Mediasval day . Nay , the sun of art set so gorgeously that men were dazzled by the glory thereof , and believed , thafc it was as sunrise , heralding a new , better phase of art , instead of its being a sunset , preluding the loss of the best the world had

seen . It behoves me , therefore , to linger over this threshold of my subject ( and nofc unwilling am I to do so , seeing that ifc is by far the pleasantest part thereof ) , and to endeavour to trace the lines of it several changes , as successively they grew fainter and fainter , together with the brightness of the evening stars of genius , which beamed like a galaxj '

through its twilight , and even occasionally long after the nightfall , until , clouded oi'er afc last , utter darkness unsued , enlivened only by the false Ai'ill-o ' -the-ivisp phantoms of rococo Avhich have been misleadina- men ever since .

This period , then , upon which I would now divell , this twilight of the "dark ages" which I ha \ r e taken for my subject , is that generally known as the Renaissance , or the revival of Classic art . It is true thafc in Italy , the whole surface of which was strewn with fragments of Roman work , Classic tradition seems always to hai'e sat like a nightmare upon its architecture . The mighty flood of life AA'hich

seems to have throbbed through the arteries of Northern Europe appears to have been checked in its passage through the gorges of the Alps , and to have exercised but slight effect below- them , and never entirely to haA'e succeeded in supplanting the influence of tho antique ; ifc succeeded in doing so to the greatest extent in the thirteenth century , and with much grace for a time fused the two stylesbut

, soon it began to hanker again after its old love , and Ave begin to find the mouldings of its Gothic buildings becoming poor ancl weak , and its parts and proportions betraying more of the Classic elements . In Venice , which , from its position , Avas nofc so strongly exposed to this influence , and which was greatly under ' that of J wth the Gothic and the

Byzantine , we find in the Doge ' s Palace a most valuable and nervous example of meditevatbuilding , unsurpassed in the boldness of its mouldings and detail ; yet , if Ave consider the general aspect of the domestic architecture of that city , Ave shall find little of the variety which was so marked a characteristic of Northern Gothic , it being similar detail to that of the Doge ' s Palace that we find repeated everyAvhere ,

ivhile that of tlie churches of the Erari and those of the same date arc strikingly inferior . In Verona we find another most valuable local development of Gothic , particularly artistic in its treatment of coloured material ancl sculpture ; still an under current of Classicism is evident throimhout Italian work . In the Cathedral of Milan it has debased it so far as to render it only worthof being a model for

y confectionery . _ In Florence and in Pisa AA'e are so entranced by the wealth displayed in their buildings , of painting and sculpture , aud precious coloured materials , that ive are consoled for the want of pure Medieval feeling and boldness in the handling of the architectural detail in such works thafc pretended to

Architecture And Archeology.

be Gothic , and in the host of false facades to the churches in the other towns , such as , we see figured in the plates of the works of Hope , Gaily Knight , and Street , we see foreshadoAved the childish shamelessness of sham ivhich mainly characterises the later works of the Renaissance , and those of tho " dark ages , " which ignores the certainty of beingfound out the instant the spectator turns the corner of the

building . In the Loggia de Lanzi , by Orcagna , Ave find distant traces of the Roman impost between the columns of the arches ; while his San Hichele , in the tabernacle and the tracery of the AvindoAvs , presents us with work , we might almost mistake for that of Batty Langley , In the pulpit by Andrew Pisano , in the cathedral of Pisa , we see in the figures and draperies of the bas-reliefs ,

evidences of an already too absorbing study of the antique , in contrast with the vigour shoivn in the beasts upon Avhich . - the alternate columns rest , where the sculptor has evidentlytreated them con amore , and rather with the traditional mediceval feeling , while fche capitals of the columns are almost as bad as the Roman composite , and the weedy apologies for cusped trefoil arches are the only and fadingtraces of Gothic forms . ( To be continued . )

The Science And Utility Of Ventilation.

THE SCIENCE AND UTILITY OF VENTILATION .

A lecture on this interesting topic was delivered at the Hanoversquare Rooms last week , by Professor Pepper , ivell known as the late scientific and enterprising conductor of the Polytechnic Institution , Regent-street . The fame of the lecturer and the importance of his subject brought together a numerous and fashionable audience , and the lecture was , in the hands of Professor Pepper , made to embrace the whole science of the subject of

ventilation in its relation to health and fche general condition of civilised , life . Tho lecturer commenced by referring to the history of A'enfcilation , and traced the tirsfc rude attempts of the Egyptians , the Grecians , and the Romans , many years before the beginning of the Christian era , to obtain \ -entilation and coolness in fche summer , and an escape for the smoke of their ( ires in the winter . Thus it appeared that the science of ventilation was early understood

, and earnest efforts ivere made to reduce it to practice by the learned men of those nations . The ancients made certain , apertures or holes in their buildings for the purpose of ventilation ; chimneys ivere not invented till about the twelfth or fourteenthcentury . Having thus complied with the . requirements of a historyloving people , Mr . Pepper proceeded to the broad and modernprinciples of ventilationivhich are based the well-knoivn

, upon law of the expansion of all bodies , solid , liquid , or gaseous , bobcat , and their contraction by cold . In illustration of this principle , a variety of interesting experiments were performed , exhibiting conclusively the action of this rigid and unswerving natural law , which , by the application of artificial means and contrivances , is made subservient to the necessities of civilisation . The importance of ventilation in its relation to human health .

was clearly pointed out and further illustrated by reference to an able paper written by Miss Florence Nightingale in the transactions of the Society for Promoting Social Science . This lady's hospital experience was most valuable in pointing out the necessit y for a continuous supply of fresh air , and plenty of it , for nothing could ' produce a more deleterious effect in the condition of the sick thana limited and impure supply of this healthy element . The danger of catching cold had been greatlexaggeratedmore especiallin a

y , y country like England , where fuel is cheap , and where the patient may be sufficiently protected by . an ample supply of clothing . Nothing could compensate for a deficient supply of air ; no artificial , means would suffice ; the only remedy was to throw open the windows , and so obtain a plentiful inlet of pure air . The hospitals in Paris , though ample , and even magnificent in their dimensions , Mr . Pepper pointed out , were incapable of conferring the whole of their and

possible intended advantages , from the simple reason that the ventilation was carried on by artificial means . In the morning , when the wards were opened , they were found to contain a close and vitiated atmosphere , which was sure to exercise an iinsalutary effect on the health of the patients . The simplest inventions in all matters of science were generally those of the widest practical utility . While discoveriesivhich had offered a broad field for

, every scientific researcher in the kingdom were floating in the minds of the astute and learned of all classes , Humphrey DaA-y electrified the savants hy the production of his miner ' s safety lamp , which was practicall y nothing more than an inclosure of the flame in a shade of fine wire gauze ; in fact , an application of a principle whose plainness and simplicity had rendered it an object of dis-