-

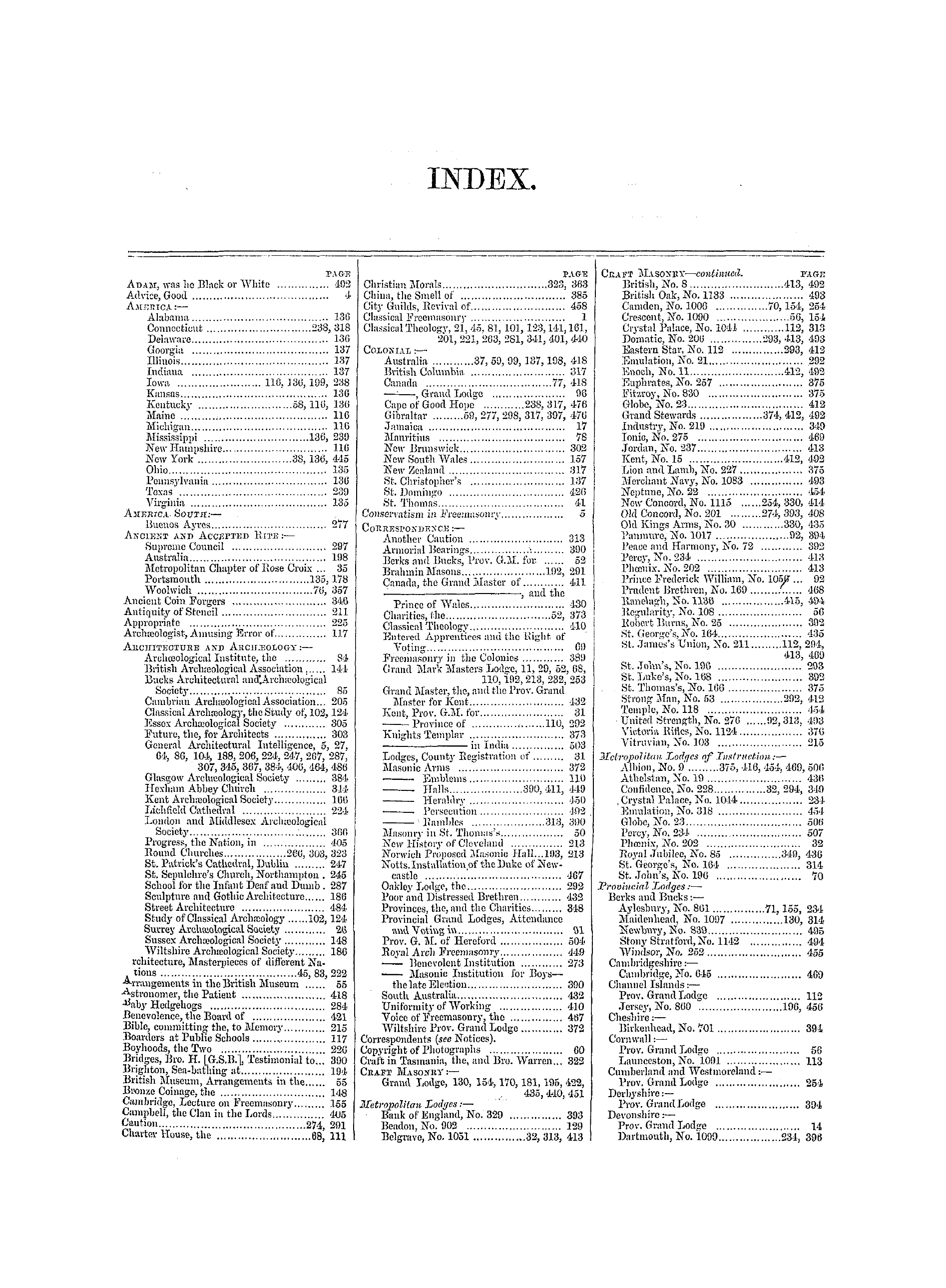

Articles/Ads

Article CLASSICAL FREEMASONRY, Page 1 of 4 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Classical Freemasonry,

CLASSICAL FREEMASONRY ,

LONDON , SATURDAY , JULY 7 , 1800 .

AS DEVELOPED IS THE POETKY OF THE ANCIENTS , BY BBO . J . P . ADAMS , M . D . AI _ THOUC . H we have no certain guide to lead ns through that labyrinth in -which we grope for the discovery of truth and are so often entangled in the maze of error when wc attempt to trace the origin of Freemasonry in the manners

of remote antiquity , yet , in what may be considered its classical period , we trust to be able to point out a moral and philosophical resemblance in the principal objects which occur in this research .

Poetry was originally of an earlier date than philosophy . The different species of the former were brought to a certain pitch of perfection before those of the latter hacl been cultivated in an equal degree . Imagination shoots forth to its full growth , and even becomes wild and luxuriant when the reasoning faculty is only beginning to bud and is wholl y

unfit to connect the series of accurate deduction . The information of the senses , from which fancy generally borrows her sublimest images , always obtains the earliest credit , and never fails to make the most lasting impressions . Plato says that poetry was originally an inspired imitation of those objects which produced either pleasure or admiration . To

excite the feelings and passions , no method could have been so effectual as that of celebrating the perfection of the powers who were supposed to preside over nature . The ode , therefore , in its first formation , was a song in honour of these powers , either sung at solemn festivals , or after the days of Amphion , who was the inventor of the lyre . Thus Horace tells us :

" Musa dedit fidibus Divos , puerosque Divorum . " " The muse to nobler subjects turned her lyre , Gods , and the sons of gods , her songs inspire . "—FHAXCKS In this infancy of the arts , when it was the business of thc muse to excite admiration by his songs , as the same po ' et informs us :

"Publica privatis secemere , sacra prophaiiis ; Concubitu prohibere vago , dare jura mantis , Oppida moliri , leges includere ligno . " "Poetic wisdom marked with happy mean , Public and private , sacred and profane , The wandering joys of lawless love supprest , AVith equal rights the wedded couple blest , Plann'd future towns and instituted laws , & c . "—EUAXCIS .

Ihis was accomplished without difficulty by the first performers in this art , because they were themselves employed in the occupation whicli thoy describe . Thoy contented themselves with painting in the simplest language tho external beauties of nature , and with conveying an image of that age in which men generally lived on tho footing

of equality—they mot on thc level and parted on tho square . In succeeding ages , when manners became more polished , and the refinements of luxury were substituted in place of the simplicity of nature , men were still fond of retaining an idea of this happy period .

Though we must acknowledge that the poetic representations of a golden age are chimerical , and that descriptions ol this kind were not always measured by the standard of truth , yet it must be allowed , at the same time , that , at a period when manners were uniform and natural , the Eclogue , whose principal excellence lies in exhibiting simple and lively

pictures of common objects and common characters , was brought at once to a state of greater perfection by the persons who introduced it , than it could have arrived at in a more improved and enlightened era . It was , therefore , to lyrical poetry that the philosophical axioms and moral ethics so conspicuous in Freemasonry owe their adornment . The poot in

this branch of his art proposed , as his principal aim , to excite admiration . ; and his mind , without the assistance of critical skill , was left to the unequal task of presenting succeeding ages to the rudiments of science . The lyric poet took a more diversified and extensive range than the pastoral poet . The former ' s imagination required a strong and steady rein to

correct its vehemence and restrain its rapidity . Though , therefore , we can conceive , without difficulty , that the latter , in his poetic effusions might contemplate only the external objects whicli were presented to him , yet we cannot so readily believe that the mind , iu framing a theogony , or in assigning distinct provinces to the powers who were supposed to preside over nature , could , in its first essays , proceed

with so calm and deliberate a pace through the fields of invention . It will be necessary to briefly sketch over the period of Grecian history , before the advent of Orpheus , that great reformer , who introduced the celebrated mysteries which were called after him , ancl in which so many points of resemblance are to be found in modern Freemasonry .

The inhabitants of Greece , who make so eminent a figure in the records of science , as well as in the history of the progression of empire , were originally a savage and lawless people , who lived in a state of war with one another , and possessed a desolate country , from which they expected to be driven by the invasion of a foreign enemy . Even after they

hacl begun to emerge from this state of absolute barbarit y , and hacl built rude cities to restrain the encroachments of : the neighbouring nations , the inland countries continued to be laid waste by the depredations of robbers , and the maritime towns were exposed to the incursions of pirates . Ingenious as the Grecians were , the terror and sus ]) enso

in which they lived for a considerable time , kept them unacquainted with the arts and sciences which were flourishing in other countries . AVhen , therefore , a genius capable of civilizing them started up , it is no wonder that they held him in the highest estimation , ancl concluded that he was either descended from or inspired by some of those divinities whose praises ho was employed in rehearsing .

Such was tho situation of Greece , when Linus , Orpheus and Musteus , the first poets whose names have reached posterity , made their appearance on the theatre of life . These writers undertook the difficult task of reforming their countrymen , and of establishing a theological and philosophical system . Authors are not agreed as to the persons who introduced into Greece the principles of philosophy . Tatia-n will have

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Classical Freemasonry,

CLASSICAL FREEMASONRY ,

LONDON , SATURDAY , JULY 7 , 1800 .

AS DEVELOPED IS THE POETKY OF THE ANCIENTS , BY BBO . J . P . ADAMS , M . D . AI _ THOUC . H we have no certain guide to lead ns through that labyrinth in -which we grope for the discovery of truth and are so often entangled in the maze of error when wc attempt to trace the origin of Freemasonry in the manners

of remote antiquity , yet , in what may be considered its classical period , we trust to be able to point out a moral and philosophical resemblance in the principal objects which occur in this research .

Poetry was originally of an earlier date than philosophy . The different species of the former were brought to a certain pitch of perfection before those of the latter hacl been cultivated in an equal degree . Imagination shoots forth to its full growth , and even becomes wild and luxuriant when the reasoning faculty is only beginning to bud and is wholl y

unfit to connect the series of accurate deduction . The information of the senses , from which fancy generally borrows her sublimest images , always obtains the earliest credit , and never fails to make the most lasting impressions . Plato says that poetry was originally an inspired imitation of those objects which produced either pleasure or admiration . To

excite the feelings and passions , no method could have been so effectual as that of celebrating the perfection of the powers who were supposed to preside over nature . The ode , therefore , in its first formation , was a song in honour of these powers , either sung at solemn festivals , or after the days of Amphion , who was the inventor of the lyre . Thus Horace tells us :

" Musa dedit fidibus Divos , puerosque Divorum . " " The muse to nobler subjects turned her lyre , Gods , and the sons of gods , her songs inspire . "—FHAXCKS In this infancy of the arts , when it was the business of thc muse to excite admiration by his songs , as the same po ' et informs us :

"Publica privatis secemere , sacra prophaiiis ; Concubitu prohibere vago , dare jura mantis , Oppida moliri , leges includere ligno . " "Poetic wisdom marked with happy mean , Public and private , sacred and profane , The wandering joys of lawless love supprest , AVith equal rights the wedded couple blest , Plann'd future towns and instituted laws , & c . "—EUAXCIS .

Ihis was accomplished without difficulty by the first performers in this art , because they were themselves employed in the occupation whicli thoy describe . Thoy contented themselves with painting in the simplest language tho external beauties of nature , and with conveying an image of that age in which men generally lived on tho footing

of equality—they mot on thc level and parted on tho square . In succeeding ages , when manners became more polished , and the refinements of luxury were substituted in place of the simplicity of nature , men were still fond of retaining an idea of this happy period .

Though we must acknowledge that the poetic representations of a golden age are chimerical , and that descriptions ol this kind were not always measured by the standard of truth , yet it must be allowed , at the same time , that , at a period when manners were uniform and natural , the Eclogue , whose principal excellence lies in exhibiting simple and lively

pictures of common objects and common characters , was brought at once to a state of greater perfection by the persons who introduced it , than it could have arrived at in a more improved and enlightened era . It was , therefore , to lyrical poetry that the philosophical axioms and moral ethics so conspicuous in Freemasonry owe their adornment . The poot in

this branch of his art proposed , as his principal aim , to excite admiration . ; and his mind , without the assistance of critical skill , was left to the unequal task of presenting succeeding ages to the rudiments of science . The lyric poet took a more diversified and extensive range than the pastoral poet . The former ' s imagination required a strong and steady rein to

correct its vehemence and restrain its rapidity . Though , therefore , we can conceive , without difficulty , that the latter , in his poetic effusions might contemplate only the external objects whicli were presented to him , yet we cannot so readily believe that the mind , iu framing a theogony , or in assigning distinct provinces to the powers who were supposed to preside over nature , could , in its first essays , proceed

with so calm and deliberate a pace through the fields of invention . It will be necessary to briefly sketch over the period of Grecian history , before the advent of Orpheus , that great reformer , who introduced the celebrated mysteries which were called after him , ancl in which so many points of resemblance are to be found in modern Freemasonry .

The inhabitants of Greece , who make so eminent a figure in the records of science , as well as in the history of the progression of empire , were originally a savage and lawless people , who lived in a state of war with one another , and possessed a desolate country , from which they expected to be driven by the invasion of a foreign enemy . Even after they

hacl begun to emerge from this state of absolute barbarit y , and hacl built rude cities to restrain the encroachments of : the neighbouring nations , the inland countries continued to be laid waste by the depredations of robbers , and the maritime towns were exposed to the incursions of pirates . Ingenious as the Grecians were , the terror and sus ]) enso

in which they lived for a considerable time , kept them unacquainted with the arts and sciences which were flourishing in other countries . AVhen , therefore , a genius capable of civilizing them started up , it is no wonder that they held him in the highest estimation , ancl concluded that he was either descended from or inspired by some of those divinities whose praises ho was employed in rehearsing .

Such was tho situation of Greece , when Linus , Orpheus and Musteus , the first poets whose names have reached posterity , made their appearance on the theatre of life . These writers undertook the difficult task of reforming their countrymen , and of establishing a theological and philosophical system . Authors are not agreed as to the persons who introduced into Greece the principles of philosophy . Tatia-n will have