-

Articles/Ads

Article THE PYTHAGOREAN TRIANGLE.* ← Page 3 of 3 Article ANCIENT RINGS. Page 1 of 3 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

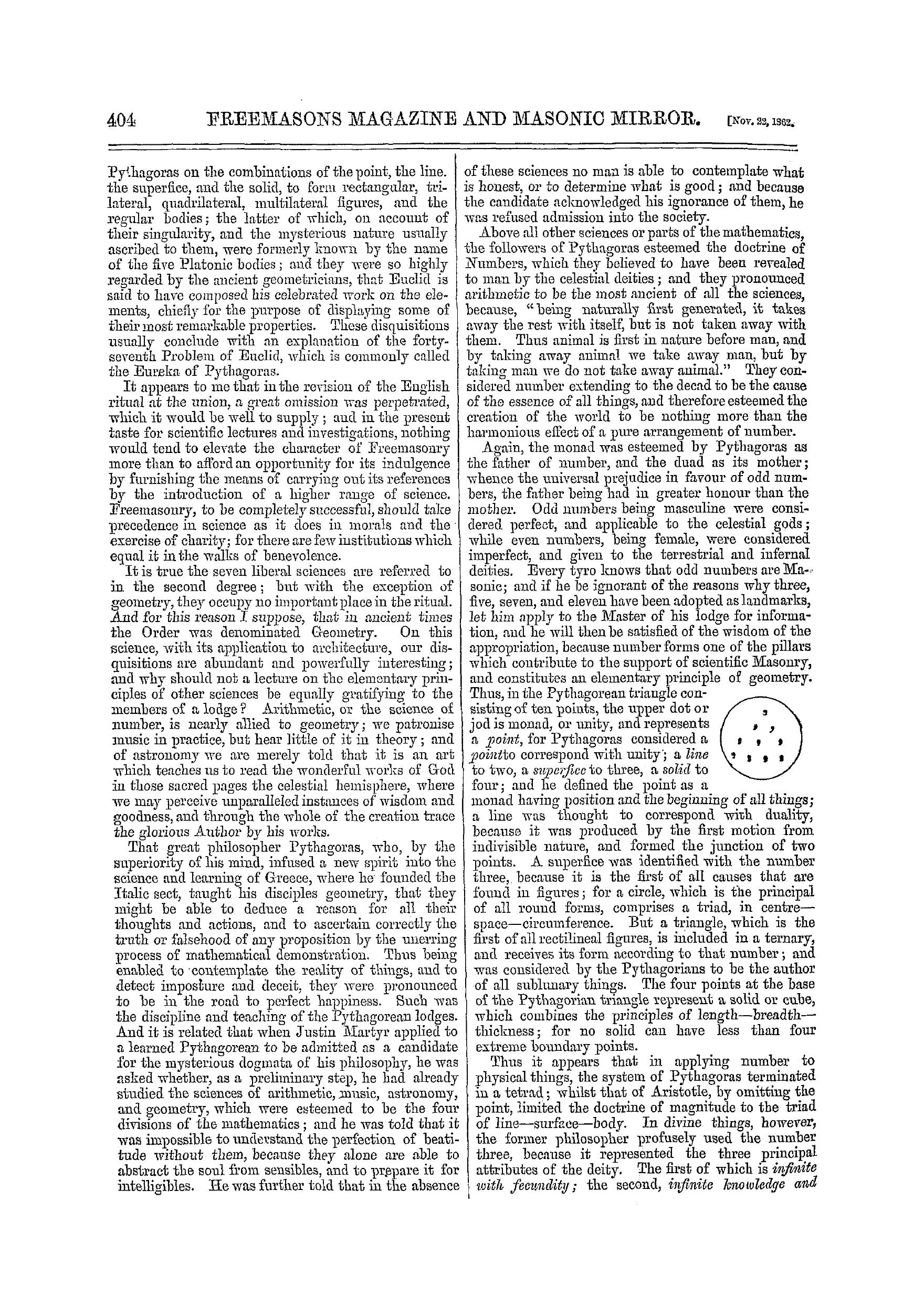

The Pythagorean Triangle.*

wisdom ; and the last , active and perceptive power . From which divine attributes the Pythagoreans and Platonists seem to have framed then- trinity of archieal hypostases , such as have the nature of principles in the universe ; and which , though they be apprehended as several distinct substances gradually

subordinate to one another , yet they many times extend to the To Theion so far as to comprehend them all within it . While employed in investigating the curious and unique properties which distinguish the Pythagorean triangle , we no longer wonder that the inhabitants

of the ancient world , in their ignorance of the mysterious secrets of science and the abstruse doctrine of causes and effects , should have ascribed to the immediate interposition of the deity those miraculous results which may be produced by an artful combination of particular numbers . Even

philosophy was staggered ; and the most refined theorists entertained singular fancies , which they were unable to solve without having recourse to supernatural agency . Hence the pseudo science of Arithmancy , or divination by numbers , became very prevalent in the ancient world' and was used b

; y Pythagoras himself as an actual emanation of the deity . By this means he pretended to fortel future events , and reduced the doctrine to a science governed by specific rules .

Ancient Rings.

ANCIENT RINGS .

In the last part of the valuable catalogue of works on loan at the South Kensington Museum , Mr . Edmund Waterton , F . S . A ., gives the following introduction to tho list of rings : — This collection of rings has been formed for the purposes of illustrating the history of finger rings from the earliest date ; consequently they have been arrangedas

, far as possible , in chronological order , and it is this peculiar feature which distinguishes the Baetyliotheca now exhibited from other existing ones , and constitutes its chief interest and value . The series commences with those of Egypt . Signet rings were much worn by the ancient Egyptians . Their rings were made of gold , of silver , of iron , and of bronze , and

were frequently set with revolving scarabcei , The lower classes wore rings of ivory and porcelain . Examples of these rings are exhibited ( Nos . 3 and 7 ) . The Greeks are supposed to have derived the use of the ring from Asia . As no mention of rings is made in Homer , Pliny concludes that in those days they were unknown . As with the Egyptians the primitive use of the ring was to si

serve as a gnet , hence , to prevent fraud , Solon enacted a law . that no seal engraver was to keep by him the impression of a ring he had cut ; whilst Pythagoras , out of reverence , forbade the images of gods to be worn in rings , In the earlier ages the rings were all of metal , then stones Were set in them . The art of gem-engraving became , in consequence much cultivated , and the Greek engravers arrived at hi

a gh degree of perfection in it . No gems certainly known to be of the Phidian period exist . It is believed that gems were not mounted in rings prior to the 62 nd Olympiad . Alexander the Great appointed Pyrgoteles to be his " engraver in ordinary , " and alone to execute his portrait in gems , just as Apelles and Lysippus in marbleGreek rings ocGur of goldof silver

. , , and of bronze ; women wore them of ivory and amber . The Greeks wore their rings generally on the annular or fourth finger of the left hand . The Etruscans were marvellously cunning goldsmiths , in which art their skill has

never been _ surpassed . They had a peculiar method of fusing and joining metals without tho use of solder , and this is the secret how to detect Etruscan jewellery in its genuine state . Gem-engraving was practised with them at a very early period ; it was rude at first , but subsequently of such a nature as to rival that of Greece . The Etruscans rarely worked in cameo ; this collection ,

however , contains an example , but in a modern setting . Rings of extraordinary beauty are found in the tombs of Etruria ; in fact , they abound , yet seldom do two occur of the same design or pattern . Silver rings are rarer than those of gold ; iron and bronze rings are for the most part gilt ; specimens of all sorts are in the collection . The so-called Egypto-Phcenician rings come from the excavations of Sardinia .

_ There is no nation with whose individual and personal history the finger ring is so closely connected as the Roman . At first the Romans wore rings of iron , the gold ring being given to those senators only who were sent abroad as ambassadors ; then it was adopted by the senators . Under the Republic and the Empire its use was regulated by laws . The ring of gold was the sign of

equestrian rank , and the Jus annuli aurei became the height of a Roman ' s ambition . Prastors and qncestors had the right of conferring the jus annuli . In later times the privilege was much abused , and in consequence the distinction became depreciated in public estimation . Then the rise of rings became immoderate in number and inconvenient in size . People no longer contented themselves

with one ring ; they sometimes wore rings on every finger , and even on every joint , One Charinus , according to Martial , wore daily a little matter of some sixty rings —that is , six to every finger ; and , what is more remarkable , he loved to sleep in them . They seem to have chosen at pleasure the devices or subjects for then , ' rings . Some wore the portraits of their ancestors , or the

representation of some event connected with their personal history , or that of their family . Every man ' s signet was his ring—the impression of it was affixed to all official acts and deeds . Hence Cicero , writing to his brother Quin tus , governor of Asia Minor , admonishes him to be careful in . the use of his signet : " Sit annulus tuus non ut vas aliqnod , sed tanquam tuipse ; non minister aliens voluntatis , sed testis tuas . " The circumstance that not merely individuals , but states , had their seals , perhaps

explains the great correspondence of many gems in rings with coin types . Roman rings occur of gold , of silver , of iron , of brass , of ivory , of lead , of amber , and of glass , and of one p iece of stone , examples of all of which , with the exception of ivory , are represented in the Dactyliotheca . The Roman rings are followed by those of the Early Christian period . Clement , of Alexandria , reproving the

heathen custom of wearing lascivious subjects cut on their rings , suggests to the Christians that they should have engraved devices of symbolic meaning , having reference to their holy faith ; such as a dove , which symbolizes life eternal and the Holy Spirit ; a palm branch , peace ; an anchor , hope ; a ship in full sail , the church ; a fish or i % ^ and the like .

, Passing over the few Gnostic rings and those of the lower empire , which need no comment , we come to the Byzantine ones . The nobles of Byzantium wore generally signet rings of metals , i . e ., unset with stones , having the letters of the cognomen arranged in the form of a cross ; of this class of signets an example is given . The are also two other rings ornamented with niello , and a signet set

with a bloodstone intaglio of St . Theodore . The Merovingians were fond of employing precious stones for the ornamentation of their jewellery , and frequently in such a manner as to represent cloisonne enamel . Some examples ai-e given , and also a remarkable specimen of filagree , or rather gold-work applique . The chief feature in Merovingian rings is that the bezels are for the most part circular , and project considerably . The goldsmith ' s craft was much cultivated not only by the Anglo-Saxons , but by the whole of the Teutonic race

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

The Pythagorean Triangle.*

wisdom ; and the last , active and perceptive power . From which divine attributes the Pythagoreans and Platonists seem to have framed then- trinity of archieal hypostases , such as have the nature of principles in the universe ; and which , though they be apprehended as several distinct substances gradually

subordinate to one another , yet they many times extend to the To Theion so far as to comprehend them all within it . While employed in investigating the curious and unique properties which distinguish the Pythagorean triangle , we no longer wonder that the inhabitants

of the ancient world , in their ignorance of the mysterious secrets of science and the abstruse doctrine of causes and effects , should have ascribed to the immediate interposition of the deity those miraculous results which may be produced by an artful combination of particular numbers . Even

philosophy was staggered ; and the most refined theorists entertained singular fancies , which they were unable to solve without having recourse to supernatural agency . Hence the pseudo science of Arithmancy , or divination by numbers , became very prevalent in the ancient world' and was used b

; y Pythagoras himself as an actual emanation of the deity . By this means he pretended to fortel future events , and reduced the doctrine to a science governed by specific rules .

Ancient Rings.

ANCIENT RINGS .

In the last part of the valuable catalogue of works on loan at the South Kensington Museum , Mr . Edmund Waterton , F . S . A ., gives the following introduction to tho list of rings : — This collection of rings has been formed for the purposes of illustrating the history of finger rings from the earliest date ; consequently they have been arrangedas

, far as possible , in chronological order , and it is this peculiar feature which distinguishes the Baetyliotheca now exhibited from other existing ones , and constitutes its chief interest and value . The series commences with those of Egypt . Signet rings were much worn by the ancient Egyptians . Their rings were made of gold , of silver , of iron , and of bronze , and

were frequently set with revolving scarabcei , The lower classes wore rings of ivory and porcelain . Examples of these rings are exhibited ( Nos . 3 and 7 ) . The Greeks are supposed to have derived the use of the ring from Asia . As no mention of rings is made in Homer , Pliny concludes that in those days they were unknown . As with the Egyptians the primitive use of the ring was to si

serve as a gnet , hence , to prevent fraud , Solon enacted a law . that no seal engraver was to keep by him the impression of a ring he had cut ; whilst Pythagoras , out of reverence , forbade the images of gods to be worn in rings , In the earlier ages the rings were all of metal , then stones Were set in them . The art of gem-engraving became , in consequence much cultivated , and the Greek engravers arrived at hi

a gh degree of perfection in it . No gems certainly known to be of the Phidian period exist . It is believed that gems were not mounted in rings prior to the 62 nd Olympiad . Alexander the Great appointed Pyrgoteles to be his " engraver in ordinary , " and alone to execute his portrait in gems , just as Apelles and Lysippus in marbleGreek rings ocGur of goldof silver

. , , and of bronze ; women wore them of ivory and amber . The Greeks wore their rings generally on the annular or fourth finger of the left hand . The Etruscans were marvellously cunning goldsmiths , in which art their skill has

never been _ surpassed . They had a peculiar method of fusing and joining metals without tho use of solder , and this is the secret how to detect Etruscan jewellery in its genuine state . Gem-engraving was practised with them at a very early period ; it was rude at first , but subsequently of such a nature as to rival that of Greece . The Etruscans rarely worked in cameo ; this collection ,

however , contains an example , but in a modern setting . Rings of extraordinary beauty are found in the tombs of Etruria ; in fact , they abound , yet seldom do two occur of the same design or pattern . Silver rings are rarer than those of gold ; iron and bronze rings are for the most part gilt ; specimens of all sorts are in the collection . The so-called Egypto-Phcenician rings come from the excavations of Sardinia .

_ There is no nation with whose individual and personal history the finger ring is so closely connected as the Roman . At first the Romans wore rings of iron , the gold ring being given to those senators only who were sent abroad as ambassadors ; then it was adopted by the senators . Under the Republic and the Empire its use was regulated by laws . The ring of gold was the sign of

equestrian rank , and the Jus annuli aurei became the height of a Roman ' s ambition . Prastors and qncestors had the right of conferring the jus annuli . In later times the privilege was much abused , and in consequence the distinction became depreciated in public estimation . Then the rise of rings became immoderate in number and inconvenient in size . People no longer contented themselves

with one ring ; they sometimes wore rings on every finger , and even on every joint , One Charinus , according to Martial , wore daily a little matter of some sixty rings —that is , six to every finger ; and , what is more remarkable , he loved to sleep in them . They seem to have chosen at pleasure the devices or subjects for then , ' rings . Some wore the portraits of their ancestors , or the

representation of some event connected with their personal history , or that of their family . Every man ' s signet was his ring—the impression of it was affixed to all official acts and deeds . Hence Cicero , writing to his brother Quin tus , governor of Asia Minor , admonishes him to be careful in . the use of his signet : " Sit annulus tuus non ut vas aliqnod , sed tanquam tuipse ; non minister aliens voluntatis , sed testis tuas . " The circumstance that not merely individuals , but states , had their seals , perhaps

explains the great correspondence of many gems in rings with coin types . Roman rings occur of gold , of silver , of iron , of brass , of ivory , of lead , of amber , and of glass , and of one p iece of stone , examples of all of which , with the exception of ivory , are represented in the Dactyliotheca . The Roman rings are followed by those of the Early Christian period . Clement , of Alexandria , reproving the

heathen custom of wearing lascivious subjects cut on their rings , suggests to the Christians that they should have engraved devices of symbolic meaning , having reference to their holy faith ; such as a dove , which symbolizes life eternal and the Holy Spirit ; a palm branch , peace ; an anchor , hope ; a ship in full sail , the church ; a fish or i % ^ and the like .

, Passing over the few Gnostic rings and those of the lower empire , which need no comment , we come to the Byzantine ones . The nobles of Byzantium wore generally signet rings of metals , i . e ., unset with stones , having the letters of the cognomen arranged in the form of a cross ; of this class of signets an example is given . The are also two other rings ornamented with niello , and a signet set

with a bloodstone intaglio of St . Theodore . The Merovingians were fond of employing precious stones for the ornamentation of their jewellery , and frequently in such a manner as to represent cloisonne enamel . Some examples ai-e given , and also a remarkable specimen of filagree , or rather gold-work applique . The chief feature in Merovingian rings is that the bezels are for the most part circular , and project considerably . The goldsmith ' s craft was much cultivated not only by the Anglo-Saxons , but by the whole of the Teutonic race