-

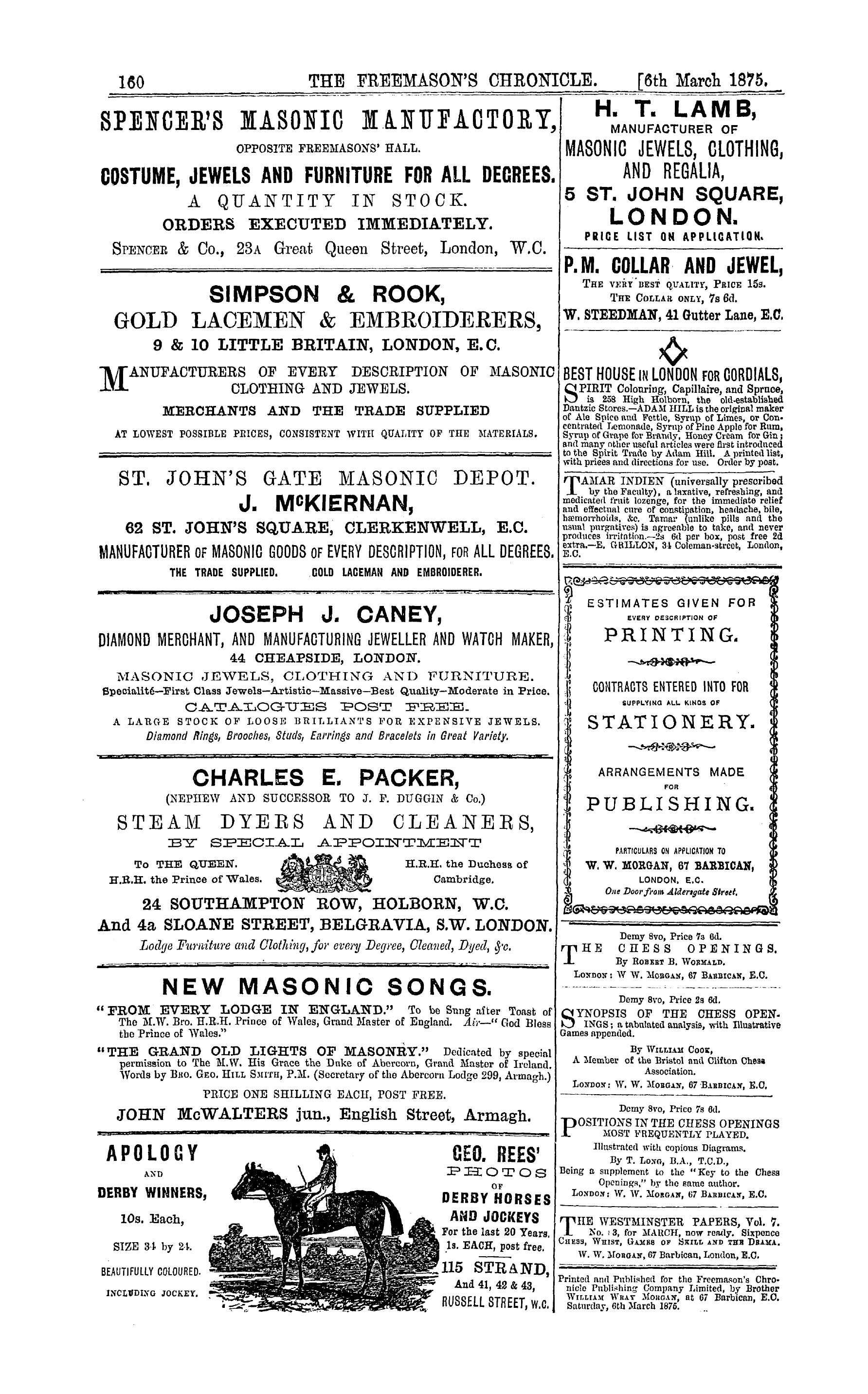

Articles/Ads

Article UNITED GRAND LODGE. ← Page 2 of 2 Article CORRESPONDENCE. Page 1 of 1 Article MASONIC MINSTRELSY. Page 1 of 1 Article REVIEWS. Page 1 of 2 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

United Grand Lodge.

Lodge of Quebec as an independent Grand Lodge ; representatives to be interchanged . A long discussion ensued on the report of the Lodge of Benevolence , wherein very largo grants were made to distressed brethren and the widows of deceased brethren . Mr . John M . Clabon ,

the president of tho Lodge of Benevolence , and Mr . Joshua Nnnn , the Vice President , stated the circumstances under which the grants had been made , and warned the brethren against falling into tho error of making the grants too large . Other Masonic business was then proceeded with , and the brethren adjourned at a lato hour .

Correspondence.

CORRESPONDENCE .

All Letters must bear the name and address of the Writer , not necessarily for publication , hut as a guarantee of good faith . We cannot undertake to return rejected communications . We do not hold ourselves responsible for the opinions of our Correspondents .

ASSISTANCE TO MASONIC CHAEITIES

To the Editor of THE FREEMASON ' S CHRONICLE . DEAR SIR AND BROTHER , —Bro . Edward Clark P . M . 1194 and 1329 , P . P . G . Sop . Wks . Middlesex , of 17 Talfonrd Road , Peckham Road , undoubtedly appreciating the great amount of good effected by Bro . Constable ' s mode of assisting the Masonic Charities , has signified his approval thereof by pursuing a similar course . He

seems , however , to have come to tho conclusion that the same amount of money might be collected , with considerably less trouble and fatigue , by charging two-shillings-and-sixpenco instead of ono shilling , as does Bro . Constable . It is gratifying that Bro . Clark , whose high position in the Craft lends additional value to his approval of this method of obtaining subscriptions , is applying his influence

and energies to its promotion . There are many who give willingly and unhesitatingly , provided they are asked to do so , bnt whoso names , cither from thoughtlessness or indolence and apathy are never seen in any list of subscribers . There arc others whose position in life does not enable them to spare sufficient to constitute what is considered a respectable donation , bnt arc nevertheless

anxious to give what they can well afford . There is a largo class of the latter , and for these , especially , subscription by ticket , with a chance of winning a Life Governorship must be in itself a groat boon . We may therefore justly express a hope that others , whoso position and influence give reasonable grounds for a prospect of success , will imitate the excellent example of Bros . Constable and Clark . Tho Masonic Charities require , and should have our constant care .

However great the amount of benefit effected by tho existing institutions , it is the undoubted duty of . every Craftsman to work with all his heart and soul to endow them with greater power . For it should ever be borno in mind that the demands for help from tho a"cd

Mason , the widow , and the orphan , are always immeasurably " in excess of the moans to bestow it . Tho resources after all are very circumscribed , and therefore any ono who applies himself to promote their extension deserves the hearty thanks of all true Masons . Yonrs fraternally , E . GOTTIIEIL .

Masonic Minstrelsy.

MASONIC MINSTRELSY .

To the Editor of Tim FREEMASON ' S CHRONICLE . SIR , —If the author of the clover stanzas entitled "My Brother " is not laughing at us , I trust he will turn his poetical talent to account for the benefit of the Order generally . Masonic minstrelsy needs much improvement , and I think the time has come when such songs as those quoted in your last article , should be banished from our

repertory . The author of " My Brother " clearly possesses a poetical turn , but his piece is better fitted for recitation than for a musical setting . Some one has remarked that the subject of a good song , must bo cither " Wine " or " Woman . " I am inclined to think that there is much truth in this . A song should deal with one thought or idea only , and it should appeal to the emotions which are common to

all men . Wine and Women are universall y appreciated hy all but a few sober fanatics who would taboo these heaven-sent solaces of poor humanity . I would suggest that our unknown author should try his hand upon either of these themes . Ho can give them a Masonic turn if lie pleases , without destroying the unity which is one of tho greatest charms of a song . One word with reference to the prevailing love for comic verse . I

believe the preference to bo bad ; a sign of frivolity and decadence . However , I can understand and appreciate . " My Brother" contains much humour , and hence I regard it as a valuable addition to our small stock of Masonic poetry , but mere farce , without either wit or humour , should be driven out of our Lodges .

Wo are a serious body , with grave ends in view ( I do not intend a pun ) , and tho verses which enliven our leisure hours should be at least tinged with " the pale cast of thought . " I am , dear Sir , yours very truly , P , \ y #

CLUB HOUSE PLATING CUIUS . —Mogul Quality , picked Is 3 d por pack , Ms per dozen packs . Do . seconds Is per pack , lis per dozen packs . If bv post Hd per pack extra . Cards for Piquet , Bezinuo , Ecart . 5 , & c , Mo"ul Quality 10 d per pack , 8 s per dozen packs . —London : W . W . Morgan , 6 / Barbican , E . C . B '

Reviews.

REVIEWS .

All Books intended for Beview should be addressed to the Editor of The Freemason ' s Chronicle , 67 Barbican , E . C . — : o : — Shakespeare Commentaries . By Dr . G . G . Gervinus , Professor at Heidelberg . Translated , under the author ' s superintendence , by F . E . Bunnett . New Edition , revised by the Translator . London : Smith , Elder and Co ., 15 Waterloo-place .

CONCLUDING NOTICE . Ono of tho most popular in tho roll of Shakespearian characters is unquestionably that of " sweet Jack Falstaff , kind Jack Falstaff , true Jack Falstaff , valiant Jack Falstaff , and , therefore , more valiant , being as he is , old Jack Falstaff . " Bnt this very popularity furnishes the strongest reason for a careful study of tho man and of the

dramas in which he is so prominent a figure . If we see him on tho stage , acted well , or even passing well only , we are intensely pleased . We langh at his drolleries , we are in love with his joviality . Wo scarcely heed his knaveries , or even the cowardice he more than once displays . Wo see in him merely a perfectly drawn , and , as such , admirable character . We know he is a true portrait of a class of

men who were common enough at the period to which he is assigned . Bnt we rarely stop to analyse the character , or to deduce the lesson which the poet intended to impress upon his hearers through its medium . In our enthusiasm for this perfection of portraiture we forget that the evil in Falstaff outweighs the good in jnst the same ratio as " the intolerable deal of sack" was out of all proportion

to " the half-pennyworth of bread . " Thus in our very admiration for the poot as the creator , tho maker of Falstaff , we do a serions injustice to his moral and aesthetic nature . It rarely occurs to us to inquire whether Shakespeare , with the vast powers he possessed , would have stooped to ennoble so worthless a personage ? Whether , indeed , he has so ennobled him ? The outer easing is so attractive

that we pause not to learn what is hidden beneath . Yet Falstaff in the two parts of Henry IV and The Merry Wives of Windsor is one of tho best practical illustrations of Shakespeare ' s value as a great moral teacher . For this reason , also , it is , perhaps with the one exception of Hamlet , one of tho best tests of a critic ' s judgment and analytical power . Hence have we reserved this for the concluding portion of our

remarks . if our author has rightly estimated this and the character of Hamlet , which aro among tho most subtle of the great poet's creations , we need hardly pause to inquire into the merits of his other analyses . Tho earlier part of tho commentary on the first part of Henry 17 . is devoted to the characters of Hotspur and Prince Henry .

Admirable as are the comments of Gervinns hereon , wo do not propose to dwell upon them , for space and time are both wanting . Pass we thenjat once to Falstaff ; " the personification of the inferior side of man , of his animal and sensual nature " ; in whom " all the spiritual part of manhonour and morality , refinement and dignity—has been early spoiled and lost . " To take tho anthor ' s sketch of his character : — "The

material part has smothered in him every passion for good or for evil ; ho was perhaps naturally good-natured , and only from trouble and bad company became ill-natured , but even this ill-nature is as short as his breath , and is never sufficiently lasting to become real malice . His form and his mere bulk condemn him to repose and love of pleasure ; laziness , epicurean comfort , cynicism , and idleness ,

which are only a recreation for his prince , are for him tho essence , nature , and business of life itself . " Later on : " His wit , the only mental gift which ho possesses , must itself serve to his subsistence ; at any rate , in the Merry Wives of Windsor , he prepares it expressly with this business-like object to escape want . Want aud necessity , it is said in Tarlton ' s 'Jests , ' is the

whetstone of -wit , and it is even so with Falstaff . This may relate especially to his ingenuity in fraudulent tricks , but the merely intellectual side of his wit may also be referred to his physical heaviness . His mere appearance attracts attention to him , and provokes men to mock him ; he affords a pictnre of tho owl bantered by the birds . This position alone calls forth , in self defence , those

passes of wit which , for the most part , do not spring from direct natural capacity . In all witty and satirical powers in men , the innate gift , generally speaking , lies in a negative realistic nature little adapted for action ; the more essential element in this power is its training and cultivation , lying , as it does , entirely in a keen , well exercised sense of comparison , and consequently in the most

versatile and manifold observation and practice . This habit became another nature ; it must have been so in Falstaff , all the more early and completely , the earlier his mere appearance provoked the attacks of wit . " Again , as to the natnre of this wit we are told : " His whole comic power lies in his unintentional wit and in his dry humour ; natural mother wit ever appears in this way ; comic

genius , like genius of every kind , moves in the nndistinguishable lino between consciousness and instinct . It is just this happy medium which Shakespeare assigned to his Falstaff ; and this medium and his position as bantering and bantered , as a mark for wit just as much as a dealer iu it himself , assigns to him the social place he always occupied . " Then , as to his

moral being , "tho words no conscience and no shame , " says the author , " express all that we require for acquaintance with him . At times indeed , he has attacks of remorse , and these make evident the man ' s better nature , even under such a material burden , is never quite lost . " To what extent this lack of all shame prevails in him is , we are told , " most glaringly depicted , when he hacked his

sword as an evidence of his heroic deeds , and by this business , and by his shameless swearing , makes even a Bardolph blush . The basis of this character is exhibited in his soliloquy concerning honour . " And again : " It is this very core , or rather nullity of his nature , his lack of honour , which places him as a great and striking contrast to the other principal character of the play . As in Percy honour and manlinesa blend into one idea , according to the notions of the age , so , on

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

United Grand Lodge.

Lodge of Quebec as an independent Grand Lodge ; representatives to be interchanged . A long discussion ensued on the report of the Lodge of Benevolence , wherein very largo grants were made to distressed brethren and the widows of deceased brethren . Mr . John M . Clabon ,

the president of tho Lodge of Benevolence , and Mr . Joshua Nnnn , the Vice President , stated the circumstances under which the grants had been made , and warned the brethren against falling into tho error of making the grants too large . Other Masonic business was then proceeded with , and the brethren adjourned at a lato hour .

Correspondence.

CORRESPONDENCE .

All Letters must bear the name and address of the Writer , not necessarily for publication , hut as a guarantee of good faith . We cannot undertake to return rejected communications . We do not hold ourselves responsible for the opinions of our Correspondents .

ASSISTANCE TO MASONIC CHAEITIES

To the Editor of THE FREEMASON ' S CHRONICLE . DEAR SIR AND BROTHER , —Bro . Edward Clark P . M . 1194 and 1329 , P . P . G . Sop . Wks . Middlesex , of 17 Talfonrd Road , Peckham Road , undoubtedly appreciating the great amount of good effected by Bro . Constable ' s mode of assisting the Masonic Charities , has signified his approval thereof by pursuing a similar course . He

seems , however , to have come to tho conclusion that the same amount of money might be collected , with considerably less trouble and fatigue , by charging two-shillings-and-sixpenco instead of ono shilling , as does Bro . Constable . It is gratifying that Bro . Clark , whose high position in the Craft lends additional value to his approval of this method of obtaining subscriptions , is applying his influence

and energies to its promotion . There are many who give willingly and unhesitatingly , provided they are asked to do so , bnt whoso names , cither from thoughtlessness or indolence and apathy are never seen in any list of subscribers . There arc others whose position in life does not enable them to spare sufficient to constitute what is considered a respectable donation , bnt arc nevertheless

anxious to give what they can well afford . There is a largo class of the latter , and for these , especially , subscription by ticket , with a chance of winning a Life Governorship must be in itself a groat boon . We may therefore justly express a hope that others , whoso position and influence give reasonable grounds for a prospect of success , will imitate the excellent example of Bros . Constable and Clark . Tho Masonic Charities require , and should have our constant care .

However great the amount of benefit effected by tho existing institutions , it is the undoubted duty of . every Craftsman to work with all his heart and soul to endow them with greater power . For it should ever be borno in mind that the demands for help from tho a"cd

Mason , the widow , and the orphan , are always immeasurably " in excess of the moans to bestow it . Tho resources after all are very circumscribed , and therefore any ono who applies himself to promote their extension deserves the hearty thanks of all true Masons . Yonrs fraternally , E . GOTTIIEIL .

Masonic Minstrelsy.

MASONIC MINSTRELSY .

To the Editor of Tim FREEMASON ' S CHRONICLE . SIR , —If the author of the clover stanzas entitled "My Brother " is not laughing at us , I trust he will turn his poetical talent to account for the benefit of the Order generally . Masonic minstrelsy needs much improvement , and I think the time has come when such songs as those quoted in your last article , should be banished from our

repertory . The author of " My Brother " clearly possesses a poetical turn , but his piece is better fitted for recitation than for a musical setting . Some one has remarked that the subject of a good song , must bo cither " Wine " or " Woman . " I am inclined to think that there is much truth in this . A song should deal with one thought or idea only , and it should appeal to the emotions which are common to

all men . Wine and Women are universall y appreciated hy all but a few sober fanatics who would taboo these heaven-sent solaces of poor humanity . I would suggest that our unknown author should try his hand upon either of these themes . Ho can give them a Masonic turn if lie pleases , without destroying the unity which is one of tho greatest charms of a song . One word with reference to the prevailing love for comic verse . I

believe the preference to bo bad ; a sign of frivolity and decadence . However , I can understand and appreciate . " My Brother" contains much humour , and hence I regard it as a valuable addition to our small stock of Masonic poetry , but mere farce , without either wit or humour , should be driven out of our Lodges .

Wo are a serious body , with grave ends in view ( I do not intend a pun ) , and tho verses which enliven our leisure hours should be at least tinged with " the pale cast of thought . " I am , dear Sir , yours very truly , P , \ y #

CLUB HOUSE PLATING CUIUS . —Mogul Quality , picked Is 3 d por pack , Ms per dozen packs . Do . seconds Is per pack , lis per dozen packs . If bv post Hd per pack extra . Cards for Piquet , Bezinuo , Ecart . 5 , & c , Mo"ul Quality 10 d per pack , 8 s per dozen packs . —London : W . W . Morgan , 6 / Barbican , E . C . B '

Reviews.

REVIEWS .

All Books intended for Beview should be addressed to the Editor of The Freemason ' s Chronicle , 67 Barbican , E . C . — : o : — Shakespeare Commentaries . By Dr . G . G . Gervinus , Professor at Heidelberg . Translated , under the author ' s superintendence , by F . E . Bunnett . New Edition , revised by the Translator . London : Smith , Elder and Co ., 15 Waterloo-place .

CONCLUDING NOTICE . Ono of tho most popular in tho roll of Shakespearian characters is unquestionably that of " sweet Jack Falstaff , kind Jack Falstaff , true Jack Falstaff , valiant Jack Falstaff , and , therefore , more valiant , being as he is , old Jack Falstaff . " Bnt this very popularity furnishes the strongest reason for a careful study of tho man and of the

dramas in which he is so prominent a figure . If we see him on tho stage , acted well , or even passing well only , we are intensely pleased . We langh at his drolleries , we are in love with his joviality . Wo scarcely heed his knaveries , or even the cowardice he more than once displays . Wo see in him merely a perfectly drawn , and , as such , admirable character . We know he is a true portrait of a class of

men who were common enough at the period to which he is assigned . Bnt we rarely stop to analyse the character , or to deduce the lesson which the poet intended to impress upon his hearers through its medium . In our enthusiasm for this perfection of portraiture we forget that the evil in Falstaff outweighs the good in jnst the same ratio as " the intolerable deal of sack" was out of all proportion

to " the half-pennyworth of bread . " Thus in our very admiration for the poot as the creator , tho maker of Falstaff , we do a serions injustice to his moral and aesthetic nature . It rarely occurs to us to inquire whether Shakespeare , with the vast powers he possessed , would have stooped to ennoble so worthless a personage ? Whether , indeed , he has so ennobled him ? The outer easing is so attractive

that we pause not to learn what is hidden beneath . Yet Falstaff in the two parts of Henry IV and The Merry Wives of Windsor is one of tho best practical illustrations of Shakespeare ' s value as a great moral teacher . For this reason , also , it is , perhaps with the one exception of Hamlet , one of tho best tests of a critic ' s judgment and analytical power . Hence have we reserved this for the concluding portion of our

remarks . if our author has rightly estimated this and the character of Hamlet , which aro among tho most subtle of the great poet's creations , we need hardly pause to inquire into the merits of his other analyses . Tho earlier part of tho commentary on the first part of Henry 17 . is devoted to the characters of Hotspur and Prince Henry .

Admirable as are the comments of Gervinns hereon , wo do not propose to dwell upon them , for space and time are both wanting . Pass we thenjat once to Falstaff ; " the personification of the inferior side of man , of his animal and sensual nature " ; in whom " all the spiritual part of manhonour and morality , refinement and dignity—has been early spoiled and lost . " To take tho anthor ' s sketch of his character : — "The

material part has smothered in him every passion for good or for evil ; ho was perhaps naturally good-natured , and only from trouble and bad company became ill-natured , but even this ill-nature is as short as his breath , and is never sufficiently lasting to become real malice . His form and his mere bulk condemn him to repose and love of pleasure ; laziness , epicurean comfort , cynicism , and idleness ,

which are only a recreation for his prince , are for him tho essence , nature , and business of life itself . " Later on : " His wit , the only mental gift which ho possesses , must itself serve to his subsistence ; at any rate , in the Merry Wives of Windsor , he prepares it expressly with this business-like object to escape want . Want aud necessity , it is said in Tarlton ' s 'Jests , ' is the

whetstone of -wit , and it is even so with Falstaff . This may relate especially to his ingenuity in fraudulent tricks , but the merely intellectual side of his wit may also be referred to his physical heaviness . His mere appearance attracts attention to him , and provokes men to mock him ; he affords a pictnre of tho owl bantered by the birds . This position alone calls forth , in self defence , those

passes of wit which , for the most part , do not spring from direct natural capacity . In all witty and satirical powers in men , the innate gift , generally speaking , lies in a negative realistic nature little adapted for action ; the more essential element in this power is its training and cultivation , lying , as it does , entirely in a keen , well exercised sense of comparison , and consequently in the most

versatile and manifold observation and practice . This habit became another nature ; it must have been so in Falstaff , all the more early and completely , the earlier his mere appearance provoked the attacks of wit . " Again , as to the natnre of this wit we are told : " His whole comic power lies in his unintentional wit and in his dry humour ; natural mother wit ever appears in this way ; comic

genius , like genius of every kind , moves in the nndistinguishable lino between consciousness and instinct . It is just this happy medium which Shakespeare assigned to his Falstaff ; and this medium and his position as bantering and bantered , as a mark for wit just as much as a dealer iu it himself , assigns to him the social place he always occupied . " Then , as to his

moral being , "tho words no conscience and no shame , " says the author , " express all that we require for acquaintance with him . At times indeed , he has attacks of remorse , and these make evident the man ' s better nature , even under such a material burden , is never quite lost . " To what extent this lack of all shame prevails in him is , we are told , " most glaringly depicted , when he hacked his

sword as an evidence of his heroic deeds , and by this business , and by his shameless swearing , makes even a Bardolph blush . The basis of this character is exhibited in his soliloquy concerning honour . " And again : " It is this very core , or rather nullity of his nature , his lack of honour , which places him as a great and striking contrast to the other principal character of the play . As in Percy honour and manlinesa blend into one idea , according to the notions of the age , so , on