Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Character, Life, And Times Of His Late Royal. Highness , By The Public Press.

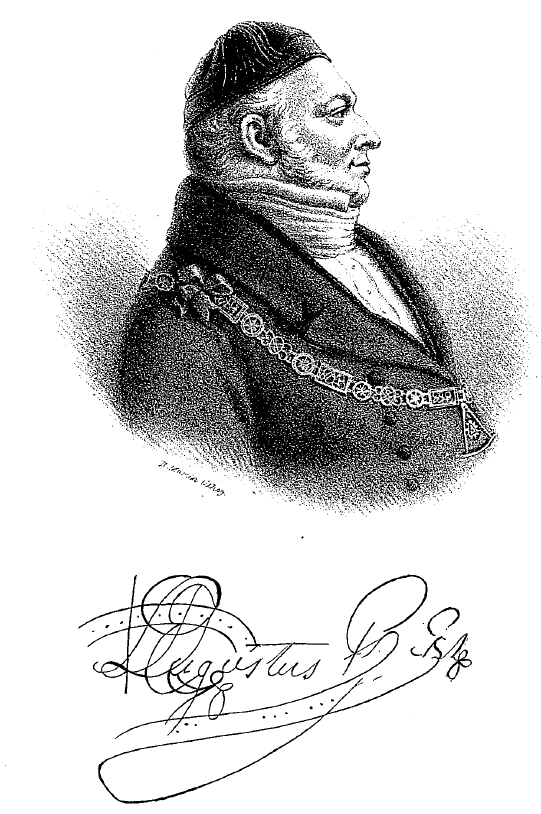

improved them by diligent and laudable cultivation . His career at the University of Gottingen , and his subsequent sojourn at Rome , gave him opportunities which were denied to his brothers . Of these advantages he fully availed himself ; and during his Continental tour he acquired that art of social intercourse , not less than that familiarity with the topics of the day , which made his conversation at once so easy and so

pleasing . It was to this residence abroad , accompanied , as it would be , by a temporary assumption of foreign habits , that we may partly ascribe that facility of manner , that affability of demeanour , and that fluency of language , which his Royal Highness never failed to exhibit at the numerous associations over which he so frequently presided . Affable , without the offensiveness of condescension ; fluent , without the

redundancy of verbiage ; easy , without the painful simulation of repose;—he combined qualities which are the most effective because they are the most rare in a chairman of public meetings . By this combination of

qualities , he certainly succeeded better than he coulcl have done b y his unaided , but undoubted , benevolence ancl singleness of purpose . These courtly virtues , which may seem easy of imitation , but which imply no small surrender of private comfort and indulgence , were , more than any political bias , calculated to endear him to the British people . But their regard for him was cemented by ties more strong

than these . He had identified himself by marriage with them . He had made himself one of them . He had overstepped the barriers of an absurd , impolitic , and indefensible but most stringent enactment , to unite his fortunes with those of a British subject ; he braved the resentment of the Crown—he risked the hereditary dignities of the succession —in order to enjoy the blessings of domestic peace with the daughter

of a British peer . It was this honest tribute to the natural supremacy of man ' s best and purest affections—this noble contempt for the paltry etiquette of Royal alliances—this constitutional vindication of a civil right , in opposition to a parliamentary prohibition , which earned for him that sympathetic favour which generally greeted him wherever he went .

And we affirm that , on this account , if on no other , he amply deserved his popularity . The Royal Marriage Act is an insult to the commonalty , to the peerage , to the Majesty of this realm . It has perpetuated a consobrinal continuity of intermarriages , which can onl y insure moral and physical evils . It was reasonable , therefore , that a prince of the blood , who had the courage to break a stupid law , for the sake of common

sense and common feeling , should receive the grateful homage of a people who pride themselves upon the robustness of their intellect and the power of their natural affections . That his Royal Highness had his faults , is only to say that he was

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Character, Life, And Times Of His Late Royal. Highness , By The Public Press.

improved them by diligent and laudable cultivation . His career at the University of Gottingen , and his subsequent sojourn at Rome , gave him opportunities which were denied to his brothers . Of these advantages he fully availed himself ; and during his Continental tour he acquired that art of social intercourse , not less than that familiarity with the topics of the day , which made his conversation at once so easy and so

pleasing . It was to this residence abroad , accompanied , as it would be , by a temporary assumption of foreign habits , that we may partly ascribe that facility of manner , that affability of demeanour , and that fluency of language , which his Royal Highness never failed to exhibit at the numerous associations over which he so frequently presided . Affable , without the offensiveness of condescension ; fluent , without the

redundancy of verbiage ; easy , without the painful simulation of repose;—he combined qualities which are the most effective because they are the most rare in a chairman of public meetings . By this combination of

qualities , he certainly succeeded better than he coulcl have done b y his unaided , but undoubted , benevolence ancl singleness of purpose . These courtly virtues , which may seem easy of imitation , but which imply no small surrender of private comfort and indulgence , were , more than any political bias , calculated to endear him to the British people . But their regard for him was cemented by ties more strong

than these . He had identified himself by marriage with them . He had made himself one of them . He had overstepped the barriers of an absurd , impolitic , and indefensible but most stringent enactment , to unite his fortunes with those of a British subject ; he braved the resentment of the Crown—he risked the hereditary dignities of the succession —in order to enjoy the blessings of domestic peace with the daughter

of a British peer . It was this honest tribute to the natural supremacy of man ' s best and purest affections—this noble contempt for the paltry etiquette of Royal alliances—this constitutional vindication of a civil right , in opposition to a parliamentary prohibition , which earned for him that sympathetic favour which generally greeted him wherever he went .

And we affirm that , on this account , if on no other , he amply deserved his popularity . The Royal Marriage Act is an insult to the commonalty , to the peerage , to the Majesty of this realm . It has perpetuated a consobrinal continuity of intermarriages , which can onl y insure moral and physical evils . It was reasonable , therefore , that a prince of the blood , who had the courage to break a stupid law , for the sake of common

sense and common feeling , should receive the grateful homage of a people who pride themselves upon the robustness of their intellect and the power of their natural affections . That his Royal Highness had his faults , is only to say that he was