-

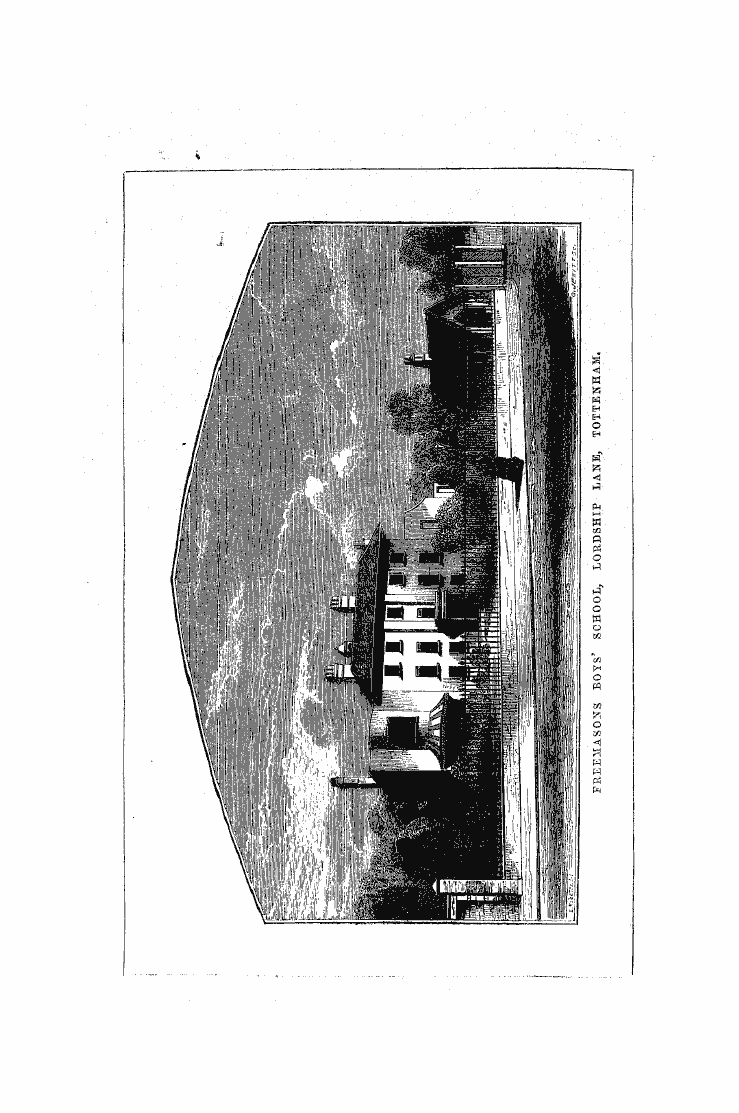

Articles/Ads

Article ANCIENT WRITERS AND MODERN PRACTICES. ← Page 7 of 9 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Ancient Writers And Modern Practices.

Mysteries }' and was only paid to the gods in those places of which they were respectively the especial patrons . " The first and original mysteries , " says Warburton , " were those of Isis and Osiris in Egypt , whence they were derived by the Greeks . ' He then mentions various places where celebrated mysteries were held , and the names of their founders , which we subjoin : —Persia , Zoroaster ; Greece , Cadmus and Inachus ; Thrace

Orpheus ; Argos , Melampus ; Bceotia , Trophonius ; Crete , Minos ; Cyprus , Cinyras ; Athens , Erectheus . " The nature and end of these were all the same—to teach the doctrine of a future state . " Here now , without going so deeply into the Masonic ritual as to print what we have no business to commit to paper , let us inquire , is not one most special object of Free-Masonry to direct our attention to the truths and doctrines of revealed

religion ( and , among them , unquestionably the doctrine here mentioned )—not , indeed , in a pagan form , as was the case in the mysteries—but as it is set forth to us in the Word of God ? Without , therefore , at all identifying Free-Masonry with the mysteries , or even

saying that it is derived from them ( indeed , we have above stated that we claim a different origin ) , we are surely justified in saying , even from the above premises , that the analogy which our opponent of the London Magazine so emphatically , and yet with merely his own ipse dixit , denies , does really exist .

Further on Warburton traces a connection between the adventures of JEneas in the abode of Pluto , in the sixth book of Virgil ' s "iEneid , " and the celebrated Eleusinian mysteries ; and here again the careful observer may trace a close analogy with Masonic doctrine .

At a future time we may enter more fully on the subject of the ancient mysteries ; let us now return to the question before us . It is true , says De Quincey , that the meaning of the Egyptian religious symbols and usages w § s kept secret from the people and from strangers . And in that sense Egypt may be said to have had mysteries ; but these mysteries involved nothing more than the essential

points of the popular religion . But here let us observe the difference of meaning attached to the word " mysteries" by De Quincey and by Warburton . The former says it w as a quasi dramatic representation of religious ideas , restricted to a few ; the latter , the secret

worship of a tutelary or patron deity—so much sought after in some places , more especially in Athens , that it was considered disgraceful not to be of the number of the initiated . We must decidedly give the preference to Warburton ' s opinion , and again observe that our author if arguing from wrong premises can scarcely arrive at a right conclusion , be his arguments ever so sound in themselves .

Third : Our author here turns his attention to Persia and Chaldsea for the origin of these orders , and says that w e shall be as much disappointed here as elsewhere . On this portion of his conjectures , however , we need not spend much time , for we , although claiming analogy with the ancient mysteries of the Egyptians and Greeks ,

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Ancient Writers And Modern Practices.

Mysteries }' and was only paid to the gods in those places of which they were respectively the especial patrons . " The first and original mysteries , " says Warburton , " were those of Isis and Osiris in Egypt , whence they were derived by the Greeks . ' He then mentions various places where celebrated mysteries were held , and the names of their founders , which we subjoin : —Persia , Zoroaster ; Greece , Cadmus and Inachus ; Thrace

Orpheus ; Argos , Melampus ; Bceotia , Trophonius ; Crete , Minos ; Cyprus , Cinyras ; Athens , Erectheus . " The nature and end of these were all the same—to teach the doctrine of a future state . " Here now , without going so deeply into the Masonic ritual as to print what we have no business to commit to paper , let us inquire , is not one most special object of Free-Masonry to direct our attention to the truths and doctrines of revealed

religion ( and , among them , unquestionably the doctrine here mentioned )—not , indeed , in a pagan form , as was the case in the mysteries—but as it is set forth to us in the Word of God ? Without , therefore , at all identifying Free-Masonry with the mysteries , or even

saying that it is derived from them ( indeed , we have above stated that we claim a different origin ) , we are surely justified in saying , even from the above premises , that the analogy which our opponent of the London Magazine so emphatically , and yet with merely his own ipse dixit , denies , does really exist .

Further on Warburton traces a connection between the adventures of JEneas in the abode of Pluto , in the sixth book of Virgil ' s "iEneid , " and the celebrated Eleusinian mysteries ; and here again the careful observer may trace a close analogy with Masonic doctrine .

At a future time we may enter more fully on the subject of the ancient mysteries ; let us now return to the question before us . It is true , says De Quincey , that the meaning of the Egyptian religious symbols and usages w § s kept secret from the people and from strangers . And in that sense Egypt may be said to have had mysteries ; but these mysteries involved nothing more than the essential

points of the popular religion . But here let us observe the difference of meaning attached to the word " mysteries" by De Quincey and by Warburton . The former says it w as a quasi dramatic representation of religious ideas , restricted to a few ; the latter , the secret

worship of a tutelary or patron deity—so much sought after in some places , more especially in Athens , that it was considered disgraceful not to be of the number of the initiated . We must decidedly give the preference to Warburton ' s opinion , and again observe that our author if arguing from wrong premises can scarcely arrive at a right conclusion , be his arguments ever so sound in themselves .

Third : Our author here turns his attention to Persia and Chaldsea for the origin of these orders , and says that w e shall be as much disappointed here as elsewhere . On this portion of his conjectures , however , we need not spend much time , for we , although claiming analogy with the ancient mysteries of the Egyptians and Greeks ,